Security: One-in-Three Journalists Regularly Face Serious Risks, but Their Level of Preparedness Varies; Most Want to Talk About It

Security: One-in-Three Journalists Regularly Face Serious Risks, but Their Level of Preparedness Varies; Most Want to Talk About It

The digital security of journalists is under threat in many parts of the world. Cyberattacks, including malware, spyware and digital surveillance increasingly target journalists and news organizations, putting their private data at risk for unauthorized access and misuse. In addition to cybersecurity breaches, journalists and news organizations are faced with new forms of online harassment and abuse. Such harassment takes many forms, but can be defined as “technology — like cellphones, computers, social media or gaming platforms — [used] to bully, threaten, or aggressively hassle someone.” Women journalists and journalists from racial, sexual or religious minority backgrounds report high rates of sexual and gendered harassment online.

There is evidence that digital and physical threats to journalists are connected, with the use of spyware connected to hundreds of acts of physical violence. Beyond physical violence, cyberthreats and online abuse affect journalists in significant ways, imposing emotional and psychological distress, resulting in the self censorship of content and causing journalists to distance themselves from their audience to avoid further harassment or threats.

This survey received responses from journalists in more than 60 countries. More than 50 responses each came from three countries: Mexico, Nigeria and the United States, each of which has a different type of government. In Reporters Without Borders’ (RSF) 2024 Press Freedom Index, the U.S. ranked 55th among 180 countries, while Nigeria and Mexico ranked 112th and 121st, respectively. Mexico is particularly dangerous for journalists; several high-profile leaks of journalists’ personal information, including from the highest levels of government, have left journalists shaken. In Nigeria, journalists often face intimidation and harassment. During protests in August 2024, at least 56 journalists were attacked and harassed. Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID)’s press attack tracker documented 135 attacks on journalists in Nigeria during 2024. The Cybercrime Act, and specifically the interpretations of cyberstalking, has been used to prosecute journalists since enforcement began in 2015.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has historically been a relatively safe country for journalists, with bedrock press freedoms. At the time of the survey, this was still the case, but more recently, the Committee to Protect Journalists has warned that the new administration is likely to curb press freedoms. In December 2024, AP News reported that journalists are anticipating renewed hostility. Initial steps in this direction have included the Executive Order “Restoring Freedom of Speech and Ending Federal Censorship” which takes aim at content moderation and fact-checking; threats to punish journalists; and actions taken to bar specific news organizations from official press conferences and spaces like the Oval Office and Air Force One.

Why we did this study

This project continues CNTI’s Defining News Initiative seeking to understand how journalism is defined today. Access to information is not just important for its own sake; it makes democracy possible. In 2024, the United Nations outlined Global Principles for Information Integrity in response to growing challenges around misinformation, disinformation and hate speech.

This survey explores (1) how current journalists view their industry, (2) their (and their organizations’) uses and perceptions of technology, (3) their perspectives on government action and cyber security and (4) their experiences with online harassment and abuse. Importantly, respondents to CNTI’s study come from a global mix of journalists that provide an international perspective on how journalists are navigating and understanding their rapidly changing industry.

For more details, see “About this study.”

How we did this

CNTI partnered with journalism organizations in several continents to share the survey with their memberships. Surveys are a snapshot of what people think at a particular moment in time. These data were collected between October 14, 2024 and December 1, 2024, which means they highlight the perspective of journalists around the world during that time frame.

These data reflect the responses collected from 433 journalists across 63 countries. Because no global census of journalists exists, no survey can be “fully representative” of all journalists. Moreover, 256 of our respondents (59%) came from three countries: Mexico, Nigeria, and the U.S.; when one of these three countries is statistically different from others in its group, we acknowledge that difference in the text.

For this section, we grouped countries by their political regime. Liberal democracies tend to have greater protections for freedom of expression than electoral democracies, and both have greater protections than autocracies. Of our survey respondents, 27% live in an autocratic country, 35% live in a liberal democracy and 39% live in an electoral democracy.

Survey questions related to cybersecurity and online abuse were analyzed based on regime type, considering the influence of different government systems on online freedom of speech and journalist safety. Government rhetoric toward journalists significantly shapes perception and the legal protections available to them. As a result, many answers vary widely depending on the respondents’ regime type.

The survey results reveal that journalists face significant cybersecurity and harassment threats all over the world and under different kinds of governments. Notably, those who frequently face high levels of risk in their work feel more prepared to address them. It also reveals that, of the journalists surveyed, about two-in-ten have experienced online impersonation.

Further, journalists have only moderate confidence in their news organizations’ ability to face external harassment. This varies based on regime type, with journalists in less democratic countries more likely to feel “very” confident. A similar trend is seen when journalists were asked if they themselves felt prepared to address both online harassment and security threats. Journalists in autocracies are more likely to say they felt very confident than those in liberal democracies.

Despite the growing digital threats to newsrooms, online safety, security and abuse is getting relatively little attention in newsrooms compared with other issues. This is true across regime types.

Journalists and their sources regularly face high levels of risk, especially in less democratic countries

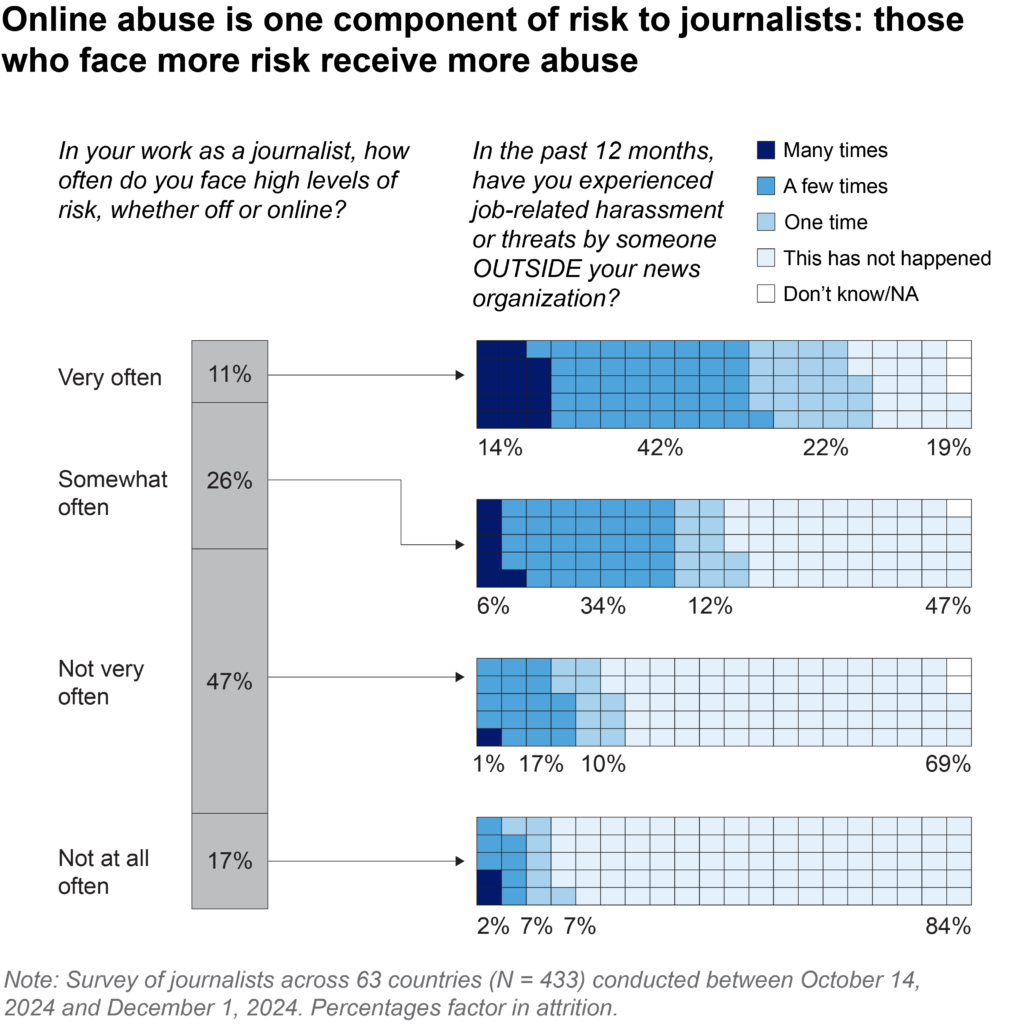

Despite the limited attention news rooms give to online abuse, many journalists report substantial levels of risks. About one-in-ten (11%) of the journalists surveyed say they face high levels of risk (on or offline) very often while 26% said they feel high levels of risk somewhat often. About half (47%) say this occurs not very often, while 17% say not at all often.

When broken down by regime type, almost a quarter (23%) of respondents from autocracies say they face high levels of risk very often, compared with just 2% of respondents in liberal democracies and 10% in electoral democracies. It is also worth noting that another 37% of journalists in electoral democracies face high risks “somewhat often,” which means that overall their experiences are more similar to journalists in autocracies than journalists in liberal democracies.

These safety concerns are not isolated to the journalists themselves; they also impact sources. Across all countries, 31% of journalists say that the sources they talk with face high levels of personal risk at least somewhat often, which is close to how they describe their own experiences. Similarly, more journalists in autocracies say that sources face risks “very often” than do journalists elsewhere.

Further, journalists who say their work is more dangerous also said they experienced more online harassment and threats. About three-quarters of journalists (78%) who say they face high levels of risk "very often" report experiencing online abuse at least once in the last year, compared with about half (51%) of those who say they face high levels of risk “somewhat often” and about one-quarter (16-28%) of those who say “not very often” or “not at all often.” That is, differences in self-reported level of risk reflect real differences on the ground.

One-in-three respondents was harassed or threatened within the last year

The kinds of risks journalists face vary, and can be physical or digital. Digital risks include cyber attacks that seek to gain access to accounts or devices, but they also take the form of online harassment or threats. All these types of risks are closely connected: private accounts often contain information like phone numbers and home addresses that can further empower harassers to escalate their threats. While cybersecurity practices can help journalists defend proactively against attacks, similarly straightforward methods to prevent harassment simply do not exist. And harassment takes a toll even on those who are prepared to face it.

About one-third (37%) of our respondents say they have experienced job-related harassment or threats by someone outside their news organization at least once in the previous year — the same proportion that say they face high risks at least somewhat often. Not all of them experienced the same amount of harassment: 4% say it happened many times, while 22% say it happened a few times and 11% say it happened one time. About half (52%) of journalists working in autocracies were harassed at least once in the past year, compared with three-in-ten in liberal democracies (34%) and electoral democracies (29%).

The most frequently reported form of harassment is threat of legal action, experienced by about a quarter (24%) of all respondents.

Almost two-in-ten journalists have faced online impersonation

As discussed in the section on technology and AI, new technologies such as AI can help journalists in their work, but it can also be a tool used against them. Survey results reveal that it is already happening: 15% of journalists surveyed say that in the past year they had learned about someone using technology to reproduce their image and 10% say they had learned about someone using technology to reproduce their voice. All in all, 17% experienced at least one of these types of impersonation.

Journalists report facing unauthorized access to accounts and online harassment

The survey offered respondents the opportunity to detail a cyber threat or breach that they had experienced in the past year. Many respondents chose not to answer, even among those who say they had these experiences. In the end we received 51 codable responses, some of which describe multiple experiences. This small number of detailed responses helps us understand the breadth of issues and some of the interconnections between cyber breaches on the one hand, and harassment and threats on the other. These examples provide some concrete context for thinking about the larger patterns in the closed-ended responses.

Looking first at the target of the attacks, the majority (32) were directed at individual journalists. We also noted nine instances where journalism organizations were the target, five unclear cases and four cases where the respondent describes a broad cyber attack (like a database breach) that did not seem to specifically target journalists.

Among the types of attacks, the most common was seeking to gain unauthorized access to devices or accounts (at least 32), which includes both accessing private messages or personal data (16 of the 32) and phishing (five of 32). The next largest group describes insults, threats or harassment (at least 17). Six of 17 were doxxed and three say that someone created fake social media profiles.

Only three respondents report DDoS attacks against their news organization, while five respondents describe other kinds of breaches, including theft of physical laptops and phones, falsified documents, being added to social media or text groups and fraudulent volunteers.

Journalists report experiencing breaches and abuse online

| Type of incident | Number reported |

|---|---|

| Unauthorized access | 32 |

| Accessing private messages or personal data | 16 |

| Phishing | 5 |

| Insults, threats, or harassment | 17 |

| Doxxing | 6 |

| Social media cloning | 3 |

| DDoS | 3 |

| Other | 5 |

On the positive side, many report that they or their news organizations were able to successfully respond to unauthorized attempts to access accounts and devices. Out of the 32 people who write about unauthorized attempts to access devices or accounts, nine of them say they were able to stop those attacks, three more report mixed experiences,1 and the other 20 say that their accounts were compromised.

One respondent’s testimony succinctly lays out the issues at hand: “We have over a hundred cyber attacks a month, but we spend a lot of money on protection, although they did manage to delete the posts from last week.” Furthermore, while most people do not identify the attacker in their response, one says outright that the sources of a breach were agents of their own government.

Journalists are fairly confident that they can respond to breaches

Respondents were asked to rank their confidence in four aspects of preparing for and responding to cyberattacks. Journalists are fairly confident about all four. The similarity in responses across all four items may suggest that journalists are broadly familiar with the concepts but may not have the knowledge they need to put it into action which suggests an opportunity for those who train journalists. Indeed, one point discussed in a recent CNTI convening on the topic was that effective cybersecurity needs to be ongoing and routine.

Journalists in less democratic countries are more confident in their ability to respond to breaches, but not to recognize them

Confidence levels in recognizing and responding to breaches vary noticeably based on regime type. Journalists in autocracies are twice as likely as journalists in either liberal or electoral democracies to say they were very confident in knowing how to respond, ensuring they have the best apps and tools and supporting colleagues. However, journalists across regime types report their ability to recognize threats similarly.

When it comes to handling online abuse, journalists are moderately confident in their news organizations

Journalists are relatively confident in their news organizations' ability to address external abuse, although journalists working in liberal democracies are less confident than their colleagues working under other government types with 11% of respondents from liberal democracies reporting they felt very confident, while 26% of respondents in electoral democracies and 30% of autocracies selected that answer.

Journalists have similar confidence in themselves as they do in their news organizations, but journalists in autocracies are most confident

Journalists display similar confidence in their own ability when asked if they felt they had the information they needed to respond to online abuse or harassment. Overall, 17% feel very confident and 7% feel not at all confident. There are some differences between regime types, with 27% of those in autocracies feeling very confident, 12-15 percentage points more than those elsewhere.

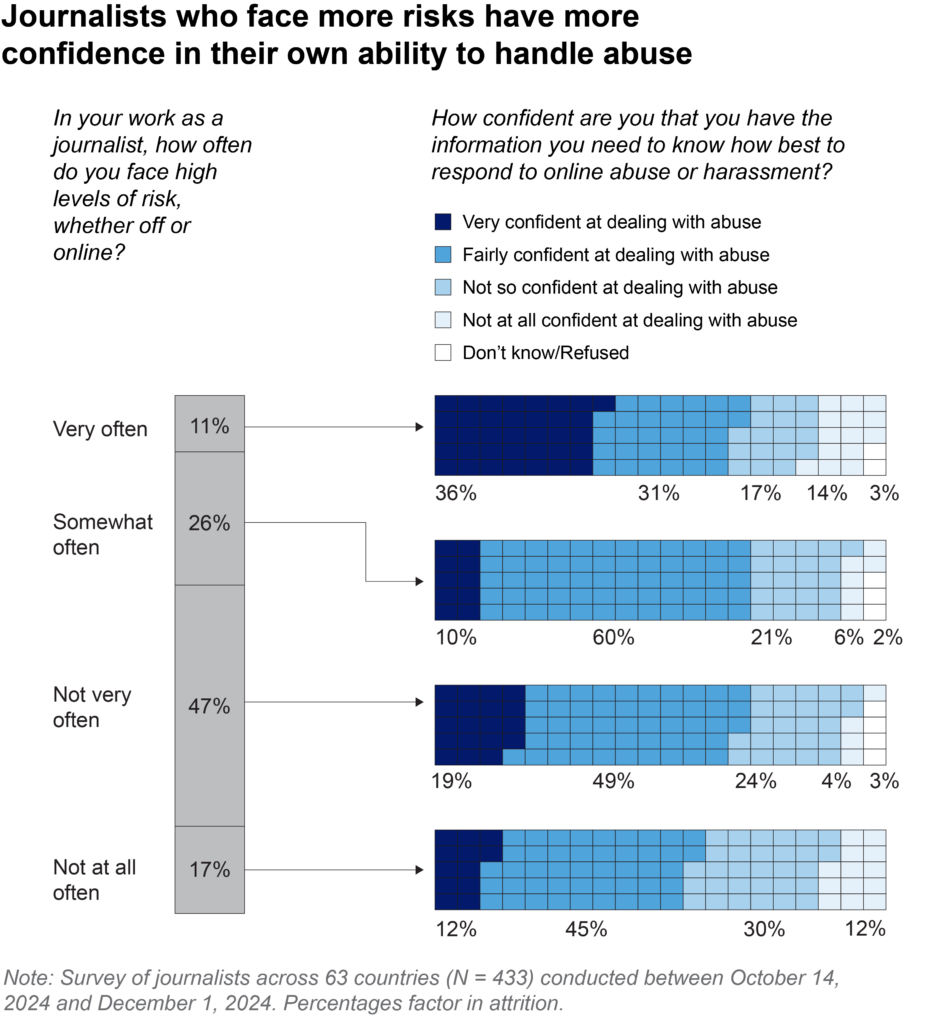

Journalists who face more risks have more confidence in their own ability to handle abuse

While facing risk does not have a strong relationship with journalists' confidence in their news organizations' ability to handle external abuse, it bears a stronger relationship to their self-confidence. Of respondents who say they face high levels of risk very often, 36% say that they are very confident they have the information they need to know how best to respond to online abuse or harassment. This confidence drops by 17 percentage points or more for everyone else, although the relationships are not fully linear.

Journalists take some cybersecurity precautions, but not always the ones experts recommend

There is no shortage of cybersecurity guides aimed at journalists, which offer many useful tools. At the same time, these guides are not always well suited to their work, particularly given the time pressure under which journalists work. In general, experts recommend:

- Using secure passwords and a password manager rather than changing passwords frequently.

- Installing software updates as soon as they become available, especially security patches.

- Using encrypted peer-to-peer apps for text messages and phone calls, as well as email encryption.

Journalists in liberal democracies update their software and passwords more frequently, but those in autocracies replace their devices more often

From the above results, we can understand that journalists are facing a multitude of threats from numerous sources, from both the public and the government. To better understand how journalists are responding, we asked about some of their practices related to technology. Journalists who took our survey change passwords and update software and hardware on devices frequently; about 40% say they do each once every few months on average, and 30% or less say they did so once every few years or when the device stops working. Of journalists in liberal democracies, 73% say they update the software/hardware on their devices at least once a year compared with 47%-51% in electoral democracies and autocracies.

This result is particularly striking because journalists in liberal democracies generally report that they face less risk than do their colleagues in autocracies. There are no financial costs associated with either of these actions, but they can be time-consuming. We also suspect that the regional differences may be due in part to differences in education and the relative professionalization of IT support.

All journalists surveyed, across regimes, replace devices less often than they update them and change passwords with 21% saying they replace them once a year or more often, while 27% say they replace them once every few years and 34% say they only replace devices when they stop working. Journalists in liberal democracies replace their devices less often than others: only about 9% say they replace devices annually or more often, compared with 29% of journalists in electoral democracies and 24% in autocracies.

Of the three actions recommended by experts, replacing devices is the only one that bears a financial cost, so it may be surprising that journalists in less democratic countries — which also tend to be less affluent — are replacing their devices more often. One explanation may be that they use less expensive devices, such as prepaid phones, which are not intended to be used for as long.

Journalists use a mix of secure and insecure methods to communicate with sources

Just as protecting their technology is crucial for journalists to prevent cyberattacks, the communication methods they use with sources are equally important for ensuring the safety of both the journalist and their source. In general, journalists communicate with sources through a range of practices. Phone calls are the most common option, followed by email, peer-to-peer encrypted messaging apps and social media.

Encrypted peer-to-peer messaging is the most secure option available, but relatively few journalists rely on it as their primary form of communication with sources. Relatively few (15%) journalists in the survey pool say these apps were their go-to. (It is difficult to classify the relative security of the most popular option, phone calls, because our questions did not differentiate between relatively insecure voice calls using phone networks and relatively secure voice calls through encrypted apps like WhatsApp or, the even more secure Signal).

The respondents choose both highly secure and relatively vulnerable methods of communication in all three regime types, although there are meaningful differences. Journalists in liberal democracies are the only group with a clear convergence: they use email far more than any other method and they also use it far more often than journalists anywhere else do.

Journalists could be better informed about the risks colleagues are facing — even though they're fairly comfortable talking about these topics

About one-in-three journalists feels very informed about online harms against their immediate colleagues, and far fewer say the same about their global ones

Sharing experiences is one way to build awareness and aptitude in response to online harms. It is striking then that even within the journalistic community — including inside one’s own newsroom, awareness about each others’ experience with online harms is limited at best. As might be expected, journalists surveyed feel more informed about online abuses and security breaches experienced by colleagues in their own news organizations than by their colleagues around the world — though neither figure is very large. This is true across regime types where journalists work.

Overall, 37% of journalists say they feel very informed about online harms experienced by colleagues in their own newsroom. This figure falls to 18% when it comes to their colleagues around the world. While most feel at least somewhat informed about each (76% and 66% respectively) there is opportunity to build awareness amongst journalists and with the public to build solidarity and collaborate on responses.

When broken down by regime type, 8% of journalists in liberal democracies feel that they are very informed about security breaches and abuse around the world, compared with 19% of those in electoral democracies and 29% in autocracies.

Strong majorities of journalists are comfortable talking about abuse, censorship and cybersecurity with their managers, although they are a little less comfortable talking about online abuse or censorship than security breaches

Strong majorities of journalists are comfortable discussing topics related to abuse, censorship and cybersecurity. At least three-quarters were comfortable discussing all four topics we asked about with managers:

- Keeping technology devices secure (88%).

- Legislation related to the news industry (84%).

- Personal experiences of online abuse or data breaches (78%).

- Government censorship or acts of violence against journalists (78%).

We see meaningful differences between regime types for personal experience of online abuse or data breaches, and government censorship or acts of violence, which are more sensitive topics. Journalists in less democratic countries are more likely to face both abuse and government censorship — and they are more hesitant to discuss these issues at work. Even so, large majorities say that they do feel comfortable discussing these issues with managers.

Journalists are similarly comfortable talking to colleagues about these topics. While respondents feel the least comfortable talking about personal experiences of online abuse or data breaches with colleagues, the differences are small. Again, strong majorities of journalists (83-90%) feel comfortable discussing even the most sensitive issues with their colleagues.

The same regime type differences also occur when talking to colleagues: journalists in less democratic countries are generally more guarded in what they are willing to discuss. For personal experiences of online abuse or data breaches, 91% of respondents in liberal democracies say that they feel comfortable discussing with colleagues, compared with 78% in electoral democracies and 79% in autocracies. For government censorship or acts of violence against journalists, 96% of those in liberal democracies say that they feel comfortable — 15 percentage points more than journalists elsewhere.

Journalists who experienced abuse did not always report it

Beyond handling device security and managing cybersecurity threats, we wanted to understand how journalists are responding to the personal threats they receive. Not everyone who had the chance to report harassment or threats did so. We asked the 113 journalists who said that they had experienced at least one type of external harassment in the last year how often they reported it to a supervisor, human resources or some other official at their news organization. Of those that said they had experienced external harassment, 40% say they reported it every time, followed by 35% some of the time and 26% none of the time. Results are consistent across regime types.2

The main reason journalists do not always report harassment is because they did not think it would make a difference. This reason far outpaces other options listed which include concerns about safety or future harassment, not knowing who to tell, because it was too emotionally difficult to discuss and concerns that sources would stop sharing information.

Continue reading:

- Overview

- Definitions: Journalists easily articulate their distinct role in society but do not think the public can

- Government: Journalists are not comfortable with government involvement

- Technology: Journalists believe technology is improving their work, but they are less sure about AI

- About this study

Read CNTI’s companion report based on surveys with representative publics in four countries.

What It Means to Do Journalism in the Age of AI

Share

Additional Work

-

World Press Freedom Day 2025: About Half of Surveyed Journalists Report Their Government Seeks Too Much Control Over Their Journalism

Three quarters of surveyed journalists do not think it is OK for their government to define journalism, regardless of perspective on government interference

-

Qué quiere el público del periodismo en la era de la IA: una encuesta en cuatro países

Tres cuartos o más de los encuestados valoran el papel del periodismo; más del 56 % dice que "la gente común" puede producir periodismo

-

Qué significa hacer periodismo en la era de la IA: Opiniones de los periodistas sobre la seguridad, la tecnología y el Gobierno

El 50 % informa haber sufrido una extralimitación del Gobierno en el último año