CNTI’s Summary

An open internet infrastructure is critical to functioning, free societies. As governments around the world increasingly turn their attention to issues of internet governance – including via efforts to tackle disinformation and protect user data – the risk of “splintered” internet experiences grows. Policy frameworks should address the distinctions among different forms of fragmentation, the (limited) scenarios in which content fragmentation is justified and how to minimize the impact of fragmentation. Internet regulation that discourages the “splinternet” distributes power outside of the government, protects and promotes individual rights (regarding encrypted and personal data) and open and transparent standards, and accounts for the global nature of the internet – particularly when it comes to the rights of journalists and citizens to communicate and share information within and across borders. Support for independent online media is critical to the protection of an open, globally connected internet.

The Issue

The rise of the global internet in its earliest days signaled a potential for free and open societies to transcend borders and connect people through digital civic spaces and to provide citizens with a global repository of information. The internet, as a public good, can provide access to reliable and independent news as well as exposure to diverse sources and perspectives. But amid changing geopolitical contexts, new technologies and the threat of online abuse and disinformation, policymakers around the world are increasingly leading governments into rethinking models of internet governance.

At the core of these discussions is who controls how the global internet functions. Often, this control is negotiated between governments and technology companies that preside over online spaces.

These political, commercial and technological pressures risk splintering the internet into a collection of different networks and user experiences based on one’s location in the world (also referred to as “fragmentation” or “balkanization”). In fact, splintering is already occurring in some places; two users may encounter wholly different internet experiences based solely on their location. While practices that result in splintering are often enacted by autocratic regimes – via rhetoric, technological developments and legislation – these types of practices are also increasingly central to internet policy debates in democratic societies.

| Open Internet | Splinternet | |

|---|---|---|

| TikTok | Blocked | |

| Wikipedia (English) | Looks like English Wikipedia, but may be in another language or may not actually be Wikipedia. | |

| Different search engine displaying government-approved sources. |

Source: Internet Society

Regulations intended to restrict and/or control online environments can involve several tactics including content takedowns, blocked or rerouted websites or platforms, government-ordered network disruptions and/or a version of the internet entirely closed-off from outside providers or services.

In weighing the challenges of this issue, it is helpful to distinguish between two types of systems: those where a “splinternet” is intentionally sought out, often to assert state control over data and digital assets or to cut off public access to independent information, and those where a “splinternet” is an unanticipated byproduct of governments’ (or even corporations’) attempts to prevent the spread of disinformation, address legitimate online harms and/or protect citizens’ data from foreign interference.

There are crucial differences between these two systems, but both introduce risks if they do not include safeguards that protect both user rights and a free flow of global information. The preservation of an open internet is especially critical for the global protection of an independent, competitive news media. Journalists depend on access to open digital communication channels to both document and distribute news, particularly when platforms have been infiltrated or blocked by the state.

It also becomes increasingly difficult for journalists to get any information across fragmented digital spaces. A number of organizations that analyze internet freedom have found there are a growing number of countries with restricted access to international information sources (see the Notable Research section for more details). These are powerful threats to press freedom and safety as well as to open public access to information.

As governments consider different approaches to digital regulation, some policy responses risk facilitating a “splinternet,” while others can protect societies from it. The challenge is to ensure that the public’s ability to use the internet to create, share and access information as well as journalists’ ability to report and distribute it is protected – both within and across borders.

At its most harmful, the “splinternet” enshrines government and/or corporate power in ways that erode human rights, including those of free expression and privacy. Greater attention to and awareness of these effects, even when unintended, will be critical for policymaking that protects and promotes an open internet.

What Makes It Complex

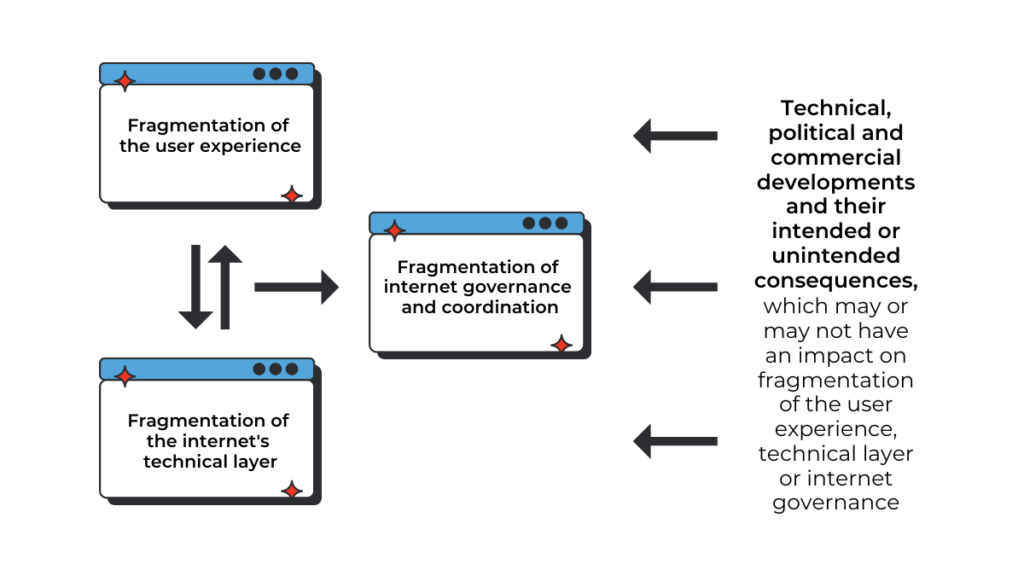

Internet “fragmentation” does not have a singular definition, so policies responding to the risks associated with fragmentation must be tailored to the particular context.

In academic and policy circles, the concept of internet “fragmentation” is broad and often contested. However, experts frequently cite two dimensions of fragmentation: technical fragmentation, referring to systems being completely disconnected from the global internet (e.g. China’s Great Firewall), and content or user experience fragmentation, referring to individuals having different online experiences depending on where they are in the world. For the latter, users may have technical connectivity, but still face restrictions in what they can access (e.g. only displaying government-approved sources in a Google search or a Twitter feed, or Netflix’s geographic controls that vary content by location). Each of these types of internet fragmentation introduces different risks, requiring different approaches to address them.

Policymakers tasked with assessing or rethinking models of internet governance face challenges in foreseeing unintended consequences of policies if they don’t have access to technical expertise in the nuances of how the internet works.

The internet is incredibly complex, so policy development requires evidence-based technical discussions in order to be effectively addressed, especially when it comes to addressing fragmentation. These global complexities include the basic technical components of the internet as a whole, how internet censorship occurs, the feasibility of digital surveillance infrastructure and the variability of fragmentation depending on its origin point(s). Origin points of fragmentation may be technical, governmental, and/or commercial:

- Technical: Changes in infrastructure that prevent systems from inter-operating and the internet from functioning consistently at all endpoints.

- Governmental: Policies (or other actions) that prevent use of the internet to create, share or access information.

- Commercial: Corporate practices that prevent use of the internet to create, share or access information.

Bans on specific digital platforms have become a common response to concerns about online safety and disinformation, but they increase the risk of internet fragmentation, threaten free expression and can encourage copycat legislation.

A growing list of governments around the world have considered or taken action against TikTok and its Beijing-based parent company ByteDance amid ongoing debates around two key issues: the potential national security risks of allowing the Chinese government to access sensitive user data and/or to use the app to distribute disinformation, and the rising concern about children’s online safety on digital platforms. Some experts argue more clarity and transparency is needed from governments’ when they cite evidence of cybersecurity risks, given that the amount and type of user data TikTok collects is not out of step with other platform companies or American data brokers. Proposed age restrictions on platforms risk violating free speech, splintering the online world and leading platforms to narrow their offerings to avoid legal ramifications. Outside of formal legislative processes, publishers, government agencies, intergovernmental agencies and universities have begun to restrict TikTok on employee devices.

These bans threaten free expression and an open internet on several fronts – most notably that they inhibit citizens’ fundamental rights to access and distribute information in democratic societies. Some legislation banning TikTok requires a technical surveillance infrastructure that would put privacy and civil liberties at risk. Further, this kind of legislation can serve as examples for autocratic governments. For example, Russia and Zambia have temporarily restricted citizens’ access to encrypted messaging apps such as Telegram and WhatsApp because the platforms refused to break end-to-end encryption, which would have allowed government agencies to access user data. Among the many complexities noted here is the question: Are there times when platform bans are justified? For instance, in Brazil, Telegram was blocked due to its failure to comply with a lawful request from the Brazilian Supreme Court. Considerations of context, along with any unintended consequences of policy proposals, must be taken into account in policy debates.

The ‘splinternet’ presents new challenges for corporations asked to comply with demands that would permit governments’ abuse of power.

At times, governments may demand (at times through legislative policy) that platforms provide private data and information on their users. If corporations adhere to these demands, they risk allowing for government abuse. If they do not, they risk breaking the law. These situations have arisen in Cambodia, India, Brazil and the U.S., which encompass many different sociopolitical contexts, including democratic jurisdictions. It is crucial to acknowledge that this issue is multifaceted, and corporations often choose specific jurisdictions and legal frameworks for market and product reasons.

Protecting an open internet is not always possible in autocratic societies, but actions taken elsewhere can still have global impact.

Citizens, advocacy groups and watchdog organizations often have limited power to stop autocratic action. However, open and globally focused policy discussions raise awareness and, as such, offer a means of pushing back against abuses of power and creating greater accountability. Further, democratic governments can impact citizens in authoritarian regimes by taking internet governance actions. For example, in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, international threats to the internet infrastructure in Russia risked cutting citizens off from accessing or sharing information outside of their country.

It is crucial to consider the impact of zero rating programs on an open internet.

Technology companies, including mobile carriers and app providers, have implemented zero rating programs (largely in developing countries) to attract customers and increase internet access. Zero rating programs, while aiming to provide access to certain services without incurring data charges, can also limit users’ experiences by creating a fragmented internet landscape. By granting free access to certain sources of content but charging for others, these programs can become the arbiters of what content is accessible, creating a tiered internet ecosystem as they promote broader adoption. In addition, many models and initiatives fall within the definition of ‘zero rating,’ and little research exists that can offer systematic evaluations of these programs. Analyzing the implications of zero rating programs is vital for understanding the challenges to achieving a connected and inclusive digital world.

The contemporary internet is still not a truly universal or open network; access and language translation vary considerably around the world.

Debates around public access to information and international connectivity standards must consider existing barriers to an open, global internet. According to the World Economic Forum, as of January 2023, nearly 3 billion people still do not have internet access. For many, this is because content is only available in a few languages despite the fact that around 6,000 languages are in use today. The top 10 languages make up more than three quarters (82%) of internet content. Even among the dominant languages, the universe of information available online differs from one language to the next. In addition to inequities in internet access and language, interconnection penetration (via the distribution of internet exchange points) and broadband access speeds vary drastically in places around the world.

State of Research

Research in the fields of internet studies and governance – particularly over the past decade – has resulted in the development of a broad set of terms reflecting similar concepts including internet governance, digital sovereignty and internet fragmentation or balkanization. Some of these terms have shifted in meaning and/or been contested as societies have undergone digital transformations. That does not mean past research loses its value, but it can make it challenging for researchers to build upon one another’s work.

To date, much of the work on internet governance has centered on authoritarian contexts (with a particular focus on China and Russia) as well as some research examining the European Union’s digital sovereignty agenda. That said, a growing segment of public-facing research conducted by independent research institutions, open internet advocacy organizations and (inter)governmental bodies (several of which we note in this primer) has focused specifically on assessing the increasing threat of the “splinternet.” This work largely relies upon expert interviews and literature reviews to arrive at a common understanding of the threats and manifestations of the “splinternet” and to recommend policies that protect an open internet.

Because these bodies of research are largely focused on either conceptualizing these issues in the context of policy or studies of critical cases, it is difficult to find systematic evidence of the scope and impact of internet governance legislation. Disagreement over what internet ‘freedom’ or ‘censorship’ entail also means there is little consensus on how to best measure them.

As platform bans become a more commonly discussed approach to addressing online safety and disinformation, research analyzing the scope and impact of these policy debates will be particularly useful. This includes how particular policy language is adopted in one context and readopted elsewhere over time and on a global scale.

Notable Studies

State of Legislation

The internet is now a central locus of global policymaking as governments increasingly debate how to regulate digital spaces within their own borders (and, at times, outside of them). Internet governance represents a broad range of stakeholders and mechanisms including national and international legislative policy as well as technological design, company policies and global regulatory institutions.

In many cases, policies or other actions that cause internet fragmentation stem from a push for “digital sovereignty,” or a government’s capacity to control or regulate its citizens’ internet content and their country’s flow of data through its technological infrastructures. Digital sovereignty is often legitimized for being in “the national interest,” though what that means varies drastically in different contexts. For instance, national interest may refer to national security or economic purposes and can take many forms within those realms.

In some cases, legislation attempts to protect societies from a “splinternet.” In others, legislation risks encouraging a “splinternet” either intentionally or unintentionally. As we note throughout this primer, this includes direct attempts to develop a closed national intranet, interventions to block access to specific platforms or sources of news and information as well as broader online governance laws that may introduce indirect consequences for free expression and an open internet. For instance, a wave of new online safety regulations in countries and regions including the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Canada promote digital privacy and other protections for citizens and simultaneously risk user experience fragmentation by enhancing controls over what and where content is shown.

Legislative efforts that protect an open internet should consult resources and recommendations provided by global internet experts. These include ensuring that governments can only collect or access online user data for transparent and legitimate purposes, promoting open standards among new technologies and platforms, protecting encryption, maintaining access to internet services and digital platforms, supporting independent online media and addressing the digital divide. It is equally critical that related policy debates at the intersection of news and technology around disinformation, artificial intelligence and algorithmic transparency consider unintended negative impacts of legislation on an open and interoperable internet.

Notable Legislation

Resources & Events

Notable Articles & Statements

Bypassing secrecy: New tools to facilitate more cross-border investigations with RTI

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (August 2023)

Safeguarding freedom of expression and access to information

UNESCO (April 2023)

Proton launches dedicated VPN servers for access to censored Deutsche Welle

PressGazette (March 2023)

It’s the great TikTok panic – and it could accelerate the end of the internet as we know it

The Guardian (March 2023)

Misguided policies the world over are slowly killing the open internet

Fortune (February 2023)

WhatsApp launches a tool to fight internet censorship

WIRED (January 2023)

Splinternet: how geopolitics is fracturing cyberspace

Polytechnique Insights (January 2023)

Internet governance doublespeak: Western governments and the open internet

Council on Foreign Relations (January 2023)

Interoperability is important for competition, consumers and the economy

Center for Democracy & Technology (January 2023)

Internet infrastructure as an emerging terrain of disinformation

Centre for International Governance Innovation (July 2022)

Biden administration risks splinternet with Europe

Tech Policy Press (July 2022)

‘Disastrous for press freedom’: What Russia’s goal of an isolated internet means for journalists

Committee to Protect Journalists (May 2022)

The declaration for the future of the internet is for wavering democracies, not China and Russia

Lawfare (May 2022)

A declaration for the future of the internet

U.S. White House and European Union (April 2022)

Blackouts

Rest of World (April 2022)

Quem defende seus dados?

InternetLab & Electronic Frontier Foundation (2022)

The internet is splintering

The New York Times (February 2021)

What is the splinternet?

The Economist (November 2016)

Key Institutions & Resources

Access Now: Nonprofit organization aiming to protect and extend global digital civil rights.

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: Nonpartisan international think tank aiming to advance international peace.

Center for Democracy & Technology: Nonprofit organization aiming to promote solutions for internet policy challenges.

Centre for International Governance Innovation: Independent, nonpartisan think tank on global governance.

Collaboration on International ICT Policy or East and Southern Africa: Works to promote effective and inclusive ICT policy and practice for improved governance, livelihoods and human rights in Africa.

Digital Watch Observatory: Observatory compiled by global policy experts to maintain a comprehensive, up-to-date summary of developments in digital policy.

Freedom on the Net: Freedom House’s annual analysis of global internet freedom.

Global Network Initiative & Country Legal Frameworks Resource: Non-governmental organization aiming to prevent internet censorship and protect individuals’ internet privacy rights.

Internet & Jurisdiction Policy Network: Multi-stakeholder organization addressing the tension between the cross-border internet and national jurisdictions.

Internet Governance Lab: American University research lab aiming to study the implications of internet governance for society and the global economy.

Internet Governance Forum: Global multi-stakeholder platform established by the United Nations that facilitates the discussion of internet policy issues.

InternetLab: Independent Brazilian research center that aims to foster academic debate around issues involving law and technology, especially internet policy.

Internet Society: Nonprofit advocacy organization aiming to support and promote the development of an open, globally connected internet.

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF): Develops voluntary internet standards for users, operators and vendors to adopt.

iWatch Africa: Non-governmental media and policy organization tracking digital rights in Africa.

Jordan Open Source Association: Nonprofit organization aiming to promote openness in technology and to defend the rights of technology users in Jordan.

Media Foundation for West Africa: Regional independent non-governmental organization with a network of national partner organizations in all 16 countries in West Africa.

NetBlocks: Independent internet monitor mapping and reporting internet blocks and global connectivity in real time.

PEN America: Nonprofit organization aiming to protect free expression in the United States and worldwide.

Research ICT Africa: Research center to inform African digital policy and data governance.

Notable Voices

Folorunso Aliu, Group Managing Director, Telnet

Jon Bateman, Senior Fellow and Co-Director, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Samantha Bradshaw, Assistant Professor, American University

Francisco Brito Cruz, Executive Director, INTERNETLAB

Laura DeNardis, Endowed Chair in Tech, Ethics, and Society, Georgetown University

Nkiru Ebenmelu, Head of Cybersecurity, Nigeria National Communication Commission

Alex Engler, Director for Technology and Democracy, The White House

Alena Epifanova, Research Fellow, German Council on Foreign Relations

Steven Feldstein, Senior Fellow, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Allie Funk, Research Director for Technology and Democracy, Freedom House

Dame Wendy Hall, Executive Director, Web Science Institute

Konstantinos Komaitis, Senior Resident Fellow at Digital Forensics Research Lab, Atlantic Council

Francesca Musiani, Research Director, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS)

Dr. Vincent Olatunji, Director of eGovernment Development and Regulations, NITDA [Nigeria]

Jason Pielemeier, Policy Director, Global Network Initiative

James Tager, Research Director, PEN America

Emily Taylor, CEO, Oxford Information Labs Limited

Tarah Wheeler, Founder, Red Queen Dynamics

Timothy Wu, Julius Silver Professor of Law, Science and Technology, Columbia Law School

Recent & Upcoming Events

“Internet for Trust” Conference

UNESCO

February 21–23, 2023 – Paris, France

RightsCon

Access Now

February 24–27, 2025 – Taipei, Taiwan

Internet Governance Forum 2024

Internet Governance Forum

December 15–19, 2024 – Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

International Conference on Evolving Internet

IARIA

March 9–13 2025 – Lisbon, Portugal

Bypassing secrecy: New tools to facilitate more cross-border investigations with RTI

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (August 2023)

Safeguarding freedom of expression and access to information

UNESCO (April 2023)

Proton launches dedicated VPN servers for access to censored Deutsche Welle

PressGazette (March 2023)

It’s the great TikTok panic – and it could accelerate the end of the internet as we know it

The Guardian (March 2023)

Misguided policies the world over are slowly killing the open internet

Fortune (February 2023)

WhatsApp launches a tool to fight internet censorship

WIRED (January 2023)

Splinternet: how geopolitics is fracturing cyberspace

Polytechnique Insights (January 2023)

Internet governance doublespeak: Western governments and the open internet

Council on Foreign Relations (January 2023)

Interoperability is important for competition, consumers and the economy

Center for Democracy & Technology (January 2023)

Internet infrastructure as an emerging terrain of disinformation

Centre for International Governance Innovation (July 2022)

Biden administration risks splinternet with Europe

Tech Policy Press (July 2022)

‘Disastrous for press freedom’: What Russia’s goal of an isolated internet means for journalists

Committee to Protect Journalists (May 2022)

The declaration for the future of the internet is for wavering democracies, not China and Russia

Lawfare (May 2022)

A declaration for the future of the internet

U.S. White House and European Union (April 2022)

Blackouts

Rest of World (April 2022)

Quem defende seus dados?

InternetLab & Electronic Frontier Foundation (2022)

The internet is splintering

The New York Times (February 2021)

What is the splinternet?

The Economist (November 2016)

Access Now: Nonprofit organization aiming to protect and extend global digital civil rights.

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: Nonpartisan international think tank aiming to advance international peace.

Center for Democracy & Technology: Nonprofit organization aiming to promote solutions for internet policy challenges.

Centre for International Governance Innovation: Independent, nonpartisan think tank on global governance.

Collaboration on International ICT Policy or East and Southern Africa: Works to promote effective and inclusive ICT policy and practice for improved governance, livelihoods and human rights in Africa.

Digital Watch Observatory: Observatory compiled by global policy experts to maintain a comprehensive, up-to-date summary of developments in digital policy.

Freedom on the Net: Freedom House’s annual analysis of global internet freedom.

Global Network Initiative & Country Legal Frameworks Resource: Non-governmental organization aiming to prevent internet censorship and protect individuals’ internet privacy rights.

Internet & Jurisdiction Policy Network: Multi-stakeholder organization addressing the tension between the cross-border internet and national jurisdictions.

Internet Governance Lab: American University research lab aiming to study the implications of internet governance for society and the global economy.

Internet Governance Forum: Global multi-stakeholder platform established by the United Nations that facilitates the discussion of internet policy issues.

InternetLab: Independent Brazilian research center that aims to foster academic debate around issues involving law and technology, especially internet policy.

Internet Society: Nonprofit advocacy organization aiming to support and promote the development of an open, globally connected internet.

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF): Develops voluntary internet standards for users, operators and vendors to adopt.

iWatch Africa: Non-governmental media and policy organization tracking digital rights in Africa.

Jordan Open Source Association: Nonprofit organization aiming to promote openness in technology and to defend the rights of technology users in Jordan.

Media Foundation for West Africa: Regional independent non-governmental organization with a network of national partner organizations in all 16 countries in West Africa.

NetBlocks: Independent internet monitor mapping and reporting internet blocks and global connectivity in real time.

PEN America: Nonprofit organization aiming to protect free expression in the United States and worldwide.

Research ICT Africa: Research center to inform African digital policy and data governance.

Folorunso Aliu, Group Managing Director, Telnet

Jon Bateman, Senior Fellow and Co-Director, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Samantha Bradshaw, Assistant Professor, American University

Francisco Brito Cruz, Executive Director, INTERNETLAB

Laura DeNardis, Endowed Chair in Tech, Ethics, and Society, Georgetown University

Nkiru Ebenmelu, Head of Cybersecurity, Nigeria National Communication Commission

Alex Engler, Director for Technology and Democracy, The White House

Alena Epifanova, Research Fellow, German Council on Foreign Relations

Steven Feldstein, Senior Fellow, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Allie Funk, Research Director for Technology and Democracy, Freedom House

Dame Wendy Hall, Executive Director, Web Science Institute

Konstantinos Komaitis, Senior Resident Fellow at Digital Forensics Research Lab, Atlantic Council

Francesca Musiani, Research Director, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS)

Dr. Vincent Olatunji, Director of eGovernment Development and Regulations, NITDA [Nigeria]

Jason Pielemeier, Policy Director, Global Network Initiative

James Tager, Research Director, PEN America

Emily Taylor, CEO, Oxford Information Labs Limited

Tarah Wheeler, Founder, Red Queen Dynamics

Timothy Wu, Julius Silver Professor of Law, Science and Technology, Columbia Law School

“Internet for Trust” Conference

UNESCO

February 21–23, 2023 – Paris, France

RightsCon

Access Now

February 24–27, 2025 – Taipei, Taiwan

Internet Governance Forum 2024

Internet Governance Forum

December 15–19 2024 – Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

International Conference on Evolving Internet

IARIA

March 9–13 2025 – Lisbon, Portugal