Introduction

As the world launches into 2024, we face a year with a record-breaking number of countries (50) holding national elections including the United States, India and Mexico. With these elections come heightened concerns about the spread of disinformation and the challenge of providing voters with fact-based news.

Discussions about how to guard against disinformation and encourage the delivery of fact-based news are critical. In working toward the best actionable outcomes, these discussions need to consider both the potential and realized impact of recent legislative policies related to this topic. This study focuses specifically on policies laid out as guarding against “fake news.”

Legislation targeting “fake news” — a contested term used to reference both news and news providers that governments (or others) reject as well as disinformation campaigns — has increased significantly over the last few years, particularly in the wake of COVID-19. This study finds that even when technically aimed at curbing disinformation, the majority of “fake news” laws, either passed or actively considered from 2020 to 2023, lessen the protection of an independent press and risk the public’s open access to a plurality of fact-based news.

Indeed, governments can — and have — used this type of legislation to label independent journalism as “fake news” or disinformation. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, among the 363 reporters jailed around the world in 2022, 39 were imprisoned for “fake news” or disinformation policy violations. Even within well-intended legislative policies, like Germany’s laws which focus on platform moderation of “illegal content” related to hate speech and Holocaust denial, concerns can arise over potential government censorship.

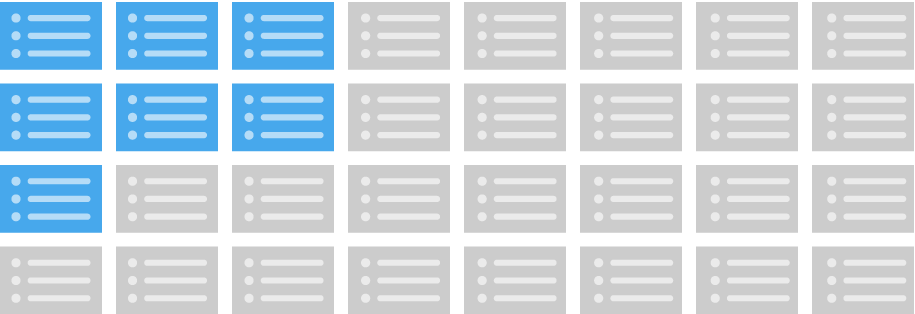

There are several pieces of legislation, such as the United Kingdom’s Online Safety Act, that are important to consider in broader policy discussions about online safety and algorithmic regulation (and are discussed in other CNTI reports) but they go beyond the scope of this study. This analysis examines the language within 32 “fake news” policies proposed or enacted from 2020 to 2023 in 31 countries, 11 of which have elections scheduled in 2024.

Overall, the study reveals that the language in the 32 pieces of legislation does little to protect fact-based news and in many cases creates significant opportunity for government control of the press. The lack of safeguards in this legislation risks curbing press and journalistic freedoms heading into a major election year. Among the key findings:

- “Fake” or “false” news is explicitly defined in less than a quarter (7/32) of this legislation. Omission of these definitions leaves them open to interpretation by whomever has oversight authority which, in these cases, is often the government itself.

- In what is very much a double-edged sword, two pieces of legislation examined here explicitly define journalism or what may be considered “real” news, one defines journalists and four define news organizations. While definitions can help protect press freedom, they can also be used as legal grounds to protect media that props up the government and ban media that does not — especially if the court’s application is also dictated by the government.

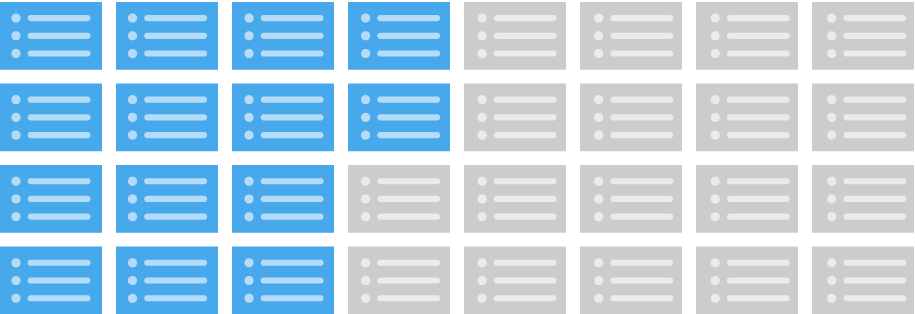

- 14 of the 32 policies clearly designate the government with the authority to decide what is or is not “fake news.” In some cases it is the central government itself and in others it is an entity within the government whose independence from the central government is often unclear. The remaining 18 policies provide either vague or no language about who has that control, ceding it to the government by default. Putting this power in the hands of the government — whether explicitly or by default — introduces greater risk of governmental press and message control.

- Although press control issues are more prevalent in the countries with autocratic rather than democratic regimes, definitional issues and a lack of clarity are found in legislation from both regime types. Of the 31 countries studied, 19 are autocratic and 11 are democracies as identified by the research organization V-Dem.1

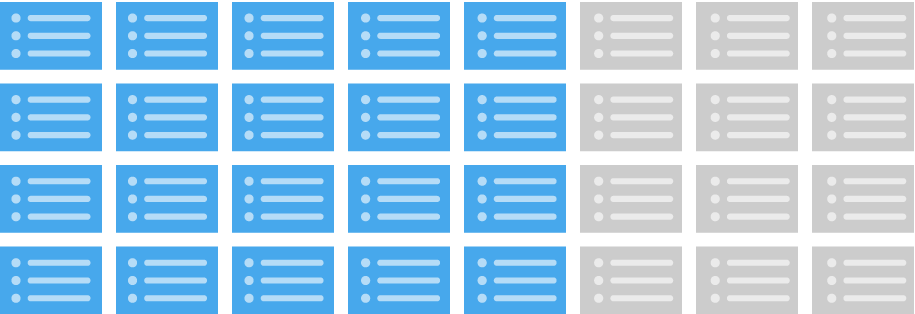

- Criminal penalties for the publication of “fake news” vary dramatically, from fines to suspension of publications to imprisonment. Among the 27 policies with clearly noted penalties, three-quarters (20 policies) include imprisonment, ranging from less than one month in Lesotho to up to 20 years in Zimbabwe.

These findings warrant concern. Vague or missing definitions can create, intentionally or not, opportunities for governments to censor opposing voices and restrict press freedom and freedom of expression. Any legislation, even if developed while under leadership that values an independent press, must account for the possibility of future regime change or legal interpretation.

Putting hard lines around false information is certainly not easy. The challenge is exacerbated when trying to discern intentional versus unintentional efforts to mislead. Legislation can be an important part of creating a digital news environment that safeguards both an independent press and the public’s access to fact-based news, but those aiming to develop policy should be aware of these challenges. CNTI offers five key questions that anyone seeking to construct policy to guard against false information in a way that safeguards an independent press and public access to a plurality of fact-based news should consider. Detailed in the “Important Policy Considerations” section of this report, they include: 1) whether policy or other non-governmental methods are the best approach for the current situation; 2) if specific independent oversight is laid out; 3) whether there are clear adjudication processes; 4) who the subject — or target — of the policy is; and 5) what future or global implications might emerge?

This report is one of many CNTI efforts to help address the challenges of today’s digital news environment in ways that safeguard an independent, competitive news media and the public’s access to a plurality of fact-based news. It is also a part of CNTI’s work in the specific area of defining journalism in our digital, global society. Any legislation related to journalism and news needs to thoroughly address the range of implications that can ensue.

APPROACHES TO “FAKE NEWS” POLICY

A substantial portion of the legislation we examine was developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, often targeting the spread of false information about the pandemic as well as information that contradicts government and public health officials. About two-fifths of the policies examined here (13/32) focus specifically on false information about COVID-19 and disputing government public health officials. For example:

- Botswana’s Emergency Powers (COVID-19) Regulations and South Africa’s amendment to its Disaster Management Act use the exact same wording, penalizing “any statement, through any medium, including social media, with the intention to deceive any other person about COVID-19; COVID-19 infection status of any person; or any measure taken by the Government to address COVID-19.”

- The Philippines’ Bayanihan To Heal As One Act penalizes “individuals or groups creating, perpetuating, or spreading false information regarding the COVID-19 crisis on social media and other platforms.”

While a narrow scope might be less susceptible to abuse, these policies nonetheless risk chilling effects on free expression or political criticism. Indeed, narrow “health” proscriptions have been used in Zimbabwe, for example, to persecute journalists questioning COVID-19 policies and exposing corruption in COVID-linked procurement practices. These topic-specific policies also suggest the potential for passing similar legislation in other topic areas deemed risky by the government.

Other recent legislation, meanwhile, include much broader — and more easily exploited — phrases about information that criticizes or harms the country’s military or economy, or sows discord:

- Greece’s legislation on false information includes “anyone who publicly or via the Internet disseminates or disseminates in any way false news that is capable of causing concern or fear among citizens or of shaking public confidence in the national economy, the country’s defense capability or public health.”

- Hungary’s legislation denotes anyone who “states or disseminates any untrue fact or any misrepresented true fact with regard to the public danger that is capable of causing disturbance or unrest in a larger group of persons at the site of public danger” is guilty of a crime.

- Myanmar’s draft legislation defines the creation of misinformation and disinformation as “causing public panic, loss of trust, or social division on cyberspace.”

Defining “Fake News”

While many countries’ legislation are similar in how they define the type of information that qualifies as false or malicious, the level of specificity varies dramatically across policies, with only occasional shared phrasing (see Table 1). A lack of clarity and use of vague language, when definitional language exists at all, carries risks for journalists and the public.

“Fake” or “false” news (sometimes referred to as disinformation, misinformation or other terminology in legislation) is explicitly defined in less than a quarter of this legislation (7/32). As is the case in disinformation studies more broadly, the question of intent often complicates definitions of “fake news,” with four of the seven seeking to separate accidental or unintentional from intentional spreading of false news (see Table 1).2 In some contexts, such as Nigeria, legislation explicitly states that it is illegal to produce “knowingly false” information, though how this definition is adjudicated is unclear.

A natural follow-up question to how false news is defined is if and how journalism — or what might be considered “real” news — is defined. Less than a quarter of these policies define any terms related to journalism. Four of the 32 policies explicitly define news organizations, while journalism (as in news content, not “fake news”) is defined in two of the 32 policies and journalists in only one.

Even when explicit definitions of journalism are present, they are often vague and thereby open to a wide array of interpretations. For example, in Togo’s 2020 Press and Communication Code, journalism is broadly defined as “original content” about current events of “general interest.” It is unclear in this legislation what qualifies as “original” or what counts as “general interest.”

References to or definitions of “journalism” or “journalists” within policy are just as — if not more — critical to fully consider than those of “fake news.” While they may be intended to protect independent, pluralistic journalism, these definitions can also be used to sanctify government control of the press.

Penalties

The criminalization of “fake news” has a long history in many countries that have experienced penal codes imposed under colonization. Similar types of penalties are embedded in many of these modern policies.

About four out of five of these policies (27/32) explicitly note criminal penalties for creating and publishing “fake news” or disinformation — most commonly fines and/or imprisonment, though some legislation includes the temporary suspension of news publications (e.g., Togo) or compulsory community service (e.g., Uzbekistan).

Among the 27 policies with clearly noted penalties, three-quarters (20 policies) include imprisonment, ranging from less than one month in Lesotho to up to 20 years in Zimbabwe.

Together, these policies reveal the serious consequences journalists face especially when legislation does not include clear oversight authorities or processes and is then abused by governments. Further, the risk of imprisonment or heavy fines may create broader impacts, discouraging independent journalists through potential consequences such as their work being labeled as “fake news.”

Important Policy Considerations

While news and news organizations are not necessarily a central consideration of “fake news” or disinformation policies, the ripple effects of these policies impact independent journalism and press freedom. Codified policies focused on news, disinformation and/or journalism — as well any language used to define these and related terms — carry tremendous power, creating opportunities for governments or other powerful actors to intentionally or unintentionally threaten the independence, diversity and freedom of the press as well as broader elements of free expression.

As Table 1 shows:

- A majority of the countries examined in this study (19/31) have some form of autocratic governance (versus 12 democracies).

- Among the 30 countries in this study that also appear in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index, more than half (17/30) rank in the bottom half of the index.

Together, these findings indicate high risks of undue political influence compounded by vague language and a lack of clear definitions and oversight processes. They also suggest that a majority of these policies may not have been intended to promote democratic values such as an independent press or free expression. Those aiming to construct policy that promotes an informed public and independent press should be aware of these conditions.

It is critical to take a careful and deliberate approach to codification of what “fake news” (real news) is and is not. This is not an easy task, as CNTI discusses in some of our issue primers, and has become even more complicated in the digital era. This study reveals five important questions to consider in policy development in this area:

- Are legislative policy or other non-governmental methods the best approach to address disinformation? The latter could include processes such as human rights or information risk assessments, content moderation or data sharing on digital platforms, news and media literacy initiatives or other related efforts. Each option, including legislative policy, has potential benefits and harms which are important to think through.

- Are specific, independent oversight of these definitions included in policy? This can be designated via self-regulatory bodies or through independent government agencies designed to protect against undue political influence.

- Are there clear adjudication processes for these definitions? Can journalists, news entities or civil society formally challenge definitional decisions by oversight bodies and if so, how?

- Who is the subject of the policy? Who would be liable? Solely individuals? Publishers? Platforms? Some combination based on the circumstances? While complex, it is important to fully consider who the law would implicate and why.

- What potential future and global implications might emerge? These decisions have global consequences, as policies in one country inherently impact those in others. And, as new technologies for disinformation and digital manipulation emerge, new tactics for addressing them may be necessary.

Appendix

Footnotes

1. One country, Vanuatu, has no noted V-Dem regime type. In this case, we have supplemented this data with indicators from the U.S. Department of State, the United Nations and Freedom House showing that Vanuatu is a parliamentary democracy and conducts democratic elections.

2. One potential reason we may not see greater similarities in phrasing is that most legislation was translated from the native language to English.

Methods and Data

This study included quantitative and qualitative analyses of 32 “fake news” legislative policies. Two content analysis coders compiled case data and coded for a range of variables including country, short and long titles of legislation, dates of legislation draft and latest update, legislation status, definitions of key terms (“news”/“journalism,” “fake news,” “journalists,” “news entities”/“publishers” and “platform”/“news intermediary”) and authorities responsible for overseeing each definition. Five test cases were coded by both coders simultaneously to assess intercoder reliability with 99.3% agreement.

The coders used a conservative approach to coding definitions. Some pieces of legislation hinted at a concept in an extraneous clause, but if the term was not explicitly defined, it was coded as “not defined.” Links to all legislation included in this research and the study’s codebook can be viewed here.

Cases representing “fake news” legislative activity from 2020 to 2023 were drawn from the Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA), LEXOTA and LupaMundi reports and databases. Additional information, including the actual drafts of legislation for analysis, was compiled from government websites and international news articles. Therefore, the analysis was limited to legislation with a full, publicly available draft or bill online. When compiling policies, some public drafts could not be found and were coded as missing cases. Google Translate was used for the 13 policies that were not available in English to keep the source of translation consistent across all pieces of legislation. All translations were also checked against ChatGPT’s translation tool to ensure that the interpretations were reliable.

Legislation analyzed per year:

| Year | Number of Bills Examined |

| 2020 | 19 |

| 2021 | 7 |

| 2022 | 5 |

| 2023 | 1 |

Legislation analyzed per geographic continent:

| Continent | Number of Bills Examined |

|---|---|

| Africa | 14 |

| Asia & Middle East | 9 |

| Australia & Oceania | 1 |

| Europe | 6 |

| North America | 1 |

| South America | 1 |

About CNTI

The Center for News, Technology & Innovation (CNTI), an independent global policy research center, seeks to encourage independent, sustainable media, maintain an open internet and foster informed public policy conversations. CNTI’s cross-industry convenings espouse evidence-based, thoughtful but challenging conversations about the issue at hand, with an eye toward feasible steps forward.

The Center for News, Technology & Innovation is a project of the Foundation for Technology, News & Public Affairs.

Acknowledgements

CNTI is generously supported by Craig Newmark Philanthropies, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Lenfest Institute for Journalism and Google.