In working towards a fully sustainable news ecosystem, CNTI’s core mission is to facilitate informed policy deliberations that safeguard an independent, diverse news media and public access to a plurality of fact-based news. To that end, we hope this examination of 23 recently enacted or proposed legislative efforts from 2018 through 2024 offers a fulsome method for analyzing possible paths forward. As with all CNTI research, this report was prepared by the research and professional staff of CNTI.

By Connie Moon Sehat, Amy Mitchell and Samuel Jens

OVERVIEW

The digital transformation of our news systems has, among other things, led to an “unbundling” of news information and the upending of journalism’s financial model in countries around the world. Many news organizations have been struggling to find a new model alongside continued newsroom layoffs and emerging news deserts.

In response, a number of legislative efforts worldwide aim to bring more funding to the journalism industry and a rebalancing of digital revenue recipients. Many recent efforts have focused on new financing streams, mainly provided by either digital platforms — who now reap more than 50% of global digital advertising revenue — or, to a lesser degree, governments.

In an effort to protect the journalism industry, authors of this legislation seem to be attempting three main goals: (1) establish funding sources for digital journalism, (2) define specific types of journalism worthy of preservation and (3) contribute to a more robust digital news environment that benefits the public and functioning, free societies.

When reviewed as a body, these legislative efforts display inventiveness and energy in creating possible solutions for journalism’s future. At the same time, while remuneration streams to support journalistic reporting are a critical component of a sustainable digital news and information environment, it is important to closely examine how legislative efforts around finance may impact other critical elements.

This study examines 23 recently enacted or proposed legislative efforts from 2018 through 2024 aimed at providing revenue streams for journalism. We hope it offers a fulsome method for analyzing possible paths forward. There are two main parts of the report:

Part One groups this legislation into seven models for financing journalism. The financing models are organized around legal mechanisms that range from an expanded view of copyright to direct support for news by platforms and governments:

| Type | Financing Model |

|---|---|

| Digital Interaction (“Usage”) |

Model 1: Ancillary Copyright around Content

|

|

Model 2: Required Negotiation with Businesses

|

|

|

Model 3: Local Usage Fee around Link Distribution

|

|

| Subsidy |

Model 4: Platform Support for News Organizations

|

|

Model 5: Government Tax Credits

Subsidy or exemption

|

|

|

Model 6: Third-Party Government Grants

|

|

| Tax |

Model 7: Hazard Tax by Government upon Platforms

|

Part Two looks at how this legislation impacts other issues critical to a sustainable news ecosystem that supports functioning, free societies. We first address an implicit yet inconsistently treated concept that emerges from this legislation: appropriate compensation, if any, for various uses of (and interactions with) digital content. This includes the notion of setting legal parameters for proper compensation that goes beyond traditional definitions of copyright. We then look at how these financially-oriented legislations impact issues within other core aspects of journalism.

Area A: The Concept of Digital Usage in Legislation

- Issue: When Is It Appropriate to Charge for Digital Usage?

- Issue: Is Compensation for Digital Usage Consistently Applied?

- Issue: Who Benefits from Appropriate Compensation?

Area B: Balancing Financial Streams with Core Elements of Journalism

- Issue: How Can We Sustain Diverse Journalism?

- Issue: How Can We Sustain Independent Journalism?

- Issue: How Can We Sustain Journalism that Serves the Public?

Conclusions

While this body of legislation seeks to provide important financial lifelines to journalism, they also reveal several areas that require further consideration in order to create a sustainable news environment that enables an informed public. Specifically:

1. Reviewing recent financial models around the world brings to light the serious questions at hand about what a sustainable news media means and what it will look like in the years to come. The funding mechanisms — ranging from ancillary copyright and platform support to tax credits and hazard taxes — each stress different elements and set different precedents. These approaches demonstrate the inventiveness of many who seek to shore up journalism, which is good to see. Yet they also pose issues and questions:

- Many pieces of legislation are proposed as temporary or triage measures to save journalism. As such, they can lack a holistic understanding of what the legislation (individually or overall) means for the flow of news information and how it should be managed long-term. This may pose problems should pieces of legislation become renewed without reflection.

- The continued development around financial models offers policy makers and stakeholders a broad array of possibilities to consider in enabling sustainability, and poses a question: how can the news environment be made sustainable? If these efforts are stop-gap measures, what should a sustainable news ecosystem look like after they are complete? If some of these efforts are not emergency measures, how well do they fit in with other elements of the ecosystem?

2. It is important to address parameters around the use and sharing of digital content, but the way this legislation has begun to define it is problematic. This set of legislation presumes there is a point at which it is appropriate to require compensation for certain digital uses of and/or interactions with content. The legislation defines that point differently and in ways that create challenges given the wide range of how digital content is accessed and shared. This is a critical construct to get right as it will have a far reaching impact. It both requires and deserves more focused deliberation. Within this legislation there is:

- Disagreement about whether basic digital interaction amounts to usage.

- Inconsistent handling and application of how digital elements such as the URLs/links and small “snippets” of content should be addressed.

- A disconnect regarding the exact beneficiaries of this proposed digital usage, whether it should be journalism organizations, journalists or any creator of content (news or not).

- No consideration of how parameters would be applied beyond the scope of news publishers and specific large technology platforms.

3. A healthy news ecosystem requires a diversity of journalistic orientations, styles and innovations to serve the full public. Protection and further advancement in this area deserves top-level attention in legislative deliberations. The ease of digital content creation provided an entryway for smaller, independent, creative and minority-focused journalism and a way for the public to access it. A piecemeal approach to supporting diversity in journalism risks taking steps backwards in this regard. Within this legislation:

- Some legislation protects midsize and larger organizations, whereas others focus on smaller entities, and the amount of money that would be distributed across the spectrum is often not clear.

- Legislation modeled around usage fees and licenses have limited references to minority ethnic media, while certain required negotiation approaches and state-funded efforts offer some explicit protection.

- The tax credit and data extraction models are the only models that explicitly define and cover local journalism.

- Only the EU Directive and New Jersey’s consortium bill explicitly speak to innovation and keeping an eye on what developments might arise in the future.

4. This legislation as a whole raises questions about journalistic independence which should be directly addressed, especially in a global environment of declining revenue and press freedoms. Legislation around digital usage aims to lessen news organizations’ dependency on technology companies. However, it is not clear whether legislation could actually increase that dependency in certain ways. Legislation also inherently increases opportunity for the government to become involved in financial remuneration for journalism entities, which makes it important to be sure journalistic independence is overtly protected. More specifically:

- There is still uncertainty about specific details of implementation when it comes to governmental oversight or the implementation of legislation within the required negotiation and usage fee models.

- Models designed around required negotiation, platform support and data extraction raise some concerns about government involvement in the mechanisms for distribution of journalistic content.

- Some of the legislation that focuses on platform support, local usage fees and hazard taxes may actually increase news organizations’ dependence on platforms even though they intend to mitigate it.

5. These legislative efforts, even when naming the public as ultimate beneficiaries, do not fully consider how to serve the public, including how the public stays informed and the kinds of journalism it values. References to the public are made throughout the legislation we reviewed, but there is little explicit explanation of how these steps will meet the public’s information needs and interests. The purpose of providing revenue streams for journalistic content — enabling an informed public and functioning, free societies — will be lost if the public does not access or value that content. Our analysis finds:

- Sometimes specific topics believed to be of interest or relevance to the public are specified for revenue support in several of the models (e.g., ancillary copyright, required negotiation and usage fees) but not all.

- Concerns about public data and privacy emerge in the usage fee and data extraction models.

- Withdrawing information from technology platforms risks less public access to information.

6. The evolution of media remuneration legislation has brought some improvements, but both journalism and the public can be better served if those involved in discussions more thoroughly and proactively evaluate the legislative options. Legislative approaches have been adapted in response to problems resulting from earlier iterations and to the different needs of the journalism industry in the contexts of particular countries or states. And in several cases, the deliberations have resulted in non-legislative agreements negotiated among the government, parts of the news industry and technology platforms. This includes for example, the emerging outcomes of negotiations around California bills AB 886 and SB 1327. Whether resulting in formal legislation or not, a more beneficial approach to policies addressing news sustainability would be to think through their goals, options and potential unintended impacts with a more global and holistic perspective.

So, what is the most effective approach, legislative or otherwise? How can we make sure enacted solutions sustain the kind of journalism and information environment that functioning, free societies need? CNTI does not lobby or propose specific legislation and instead is dedicated to helping surface these answers through further research and collaborative, multi-stakeholder discussions, which we look forward to advancing in the months to come with a few discussion guideposts offered at the conclusion of this report.

Find more details about this study’s methodology and data here.

Part One: Legal Mechanisms for Journalism Financing

As the first step in this analysis, we identified seven core legislative models of journalism remuneration that have been put forward which use different legal mechanisms for financial streams. We lay out each model and note cases where pieces of legislation have built off of each other over time. As bills are proposed and others amended in an effort to sustain the news ecosystem, these models offer a framework for evaluating their potential benefits and risks.

Different from broader frameworks, this analysis is tightly focused on specific bills and their structures of financial remuneration. We have focused on efforts made between 2018 – 2024 including many state-level bills in the United States. We did not capture measures related to direct governmental advertising spending or incentives and regulation regarding the ownership of news organizations, but we included links to these efforts in the methodology. There are also ongoing antitrust cases against technology companies as well as aspects of public policy in the civil society ecosystem, such as the US 2019 Covid Relief Bill, that can have a material impact on news finances, but are outside the direct scope of this research.

Some laws and bills apply more than one model. For example, a draft bill in Brazil includes language about bargaining which stemmed from Australia’s bill in 2021. Hybrid legislation has been marked with an asterisk (*). In addition, while some legislative examples may not have been enacted, they often remain under consideration so have been included in this report.

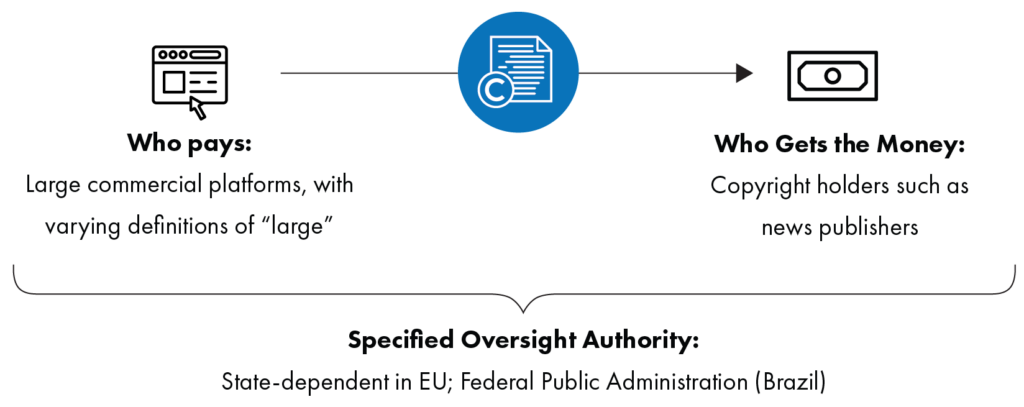

Model 1: Ancillary Copyright around Content

Legal Mechanism: Payment for the “use” of copyrighted materials, including journalism, when online on a mass scale

Financial Structure:

Journalism Defined/Protected As: Copyrighted content or copyrighted publication in any form; hyperlinking is exempted

Legislation with this model: European Union [2019/790] (2019, enacted); Brazil [PL 2370] (2023, proposed)*

An ancillary view of copyright is based on the premise that content made available online, such as journalism articles, are being utilized digitally in ways not well captured in earlier or existing copyright law. According to this argument, content creators such as news organizations are not being adequately compensated. Therefore, laws and policies that follow this model attempt to expand the ways that digital platforms, particularly large-scale ones, make use of content even if they are not necessarily quoting directly from that content.

The European Union’s (EU) 2019/790 Directive exemplifies this model. Before its enactment, several efforts across Europe attempted to expand copyright. For example, Germany’s 2013 Leistungsschutzrecht für Presseverleger (Ancillary Copyright for Press Publishers) allowed for short quotes of undefined length or “snippets” of news to warrant compensation. Though the German law was enacted, attempts to leverage the law were unsuccessful in practice. Publisher Axel Springer restricted the snippets from Google in 2014, for example, causing a plunge in traffic to its news sites. Springer lifted its restriction within two weeks.

The 2019 EU Directive has taken a slightly different approach. Sensitive to potential issues of copyright overreach, the Directive makes clear that elements such as URLs are not in themselves copyrightable; it also directs states to include text and data mining exceptions or limitations. Very short extracts also appear to be available for general use, though the Directive does not define “short.” In addition, in recognition of the ways online environments work, the Directive seeks to protect the open sharing of scientific, cultural and non-commercial information and does not mandate compensation for solely indexing of or access to that content. The Directive has enabled protections around the online use of content for 2 years (Article 15, para 4) and thumbnail images and short texts can be considered copyrightable. Due to EU procedures, some member states have yet to define and enact their own laws, yet this Directive has resulted in agreements between publishers in Germany, France, Spain and others.

There is vagueness in the Directive regarding exactly what content is being protected, a vagueness echoed in recent efforts to create a similar law in Brazil. Brazil’s PL 2370/2019 is still undergoing debate and revision, but at the time of this report, it has been encouraging negotiation between larger commercial platforms (with over 2 million users in the country) and creators of journalistic content whenever “elements, summaries, or […] other tools to expand any information present” are employed or added.

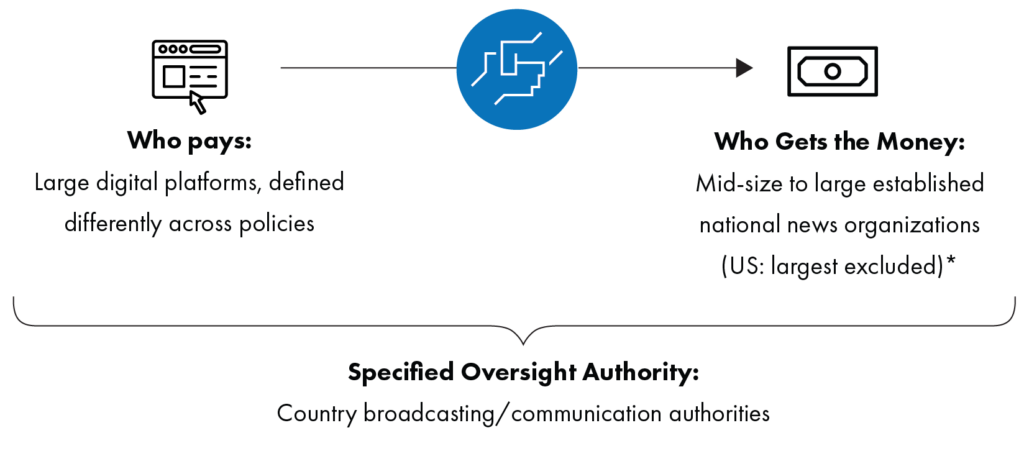

Model 2: Required Negotiation with Businesses

Legal Mechanism: Negotiation support for news organizations given digital platforms’ broad background access to news content

Financial Structure:

Journalism Defined/Protected As: Content or publication/organizations (US: journalist*)

Legislation with this model: Australia [Act No. 21] (2021, enacted but no designees); Brazil [PL 2370] (2023, proposed), Canada [C-18] (2023, enacted); New Zealand [GB 278-1] (2023, proposed); United States [S. 1094] (2023, proposed); possibly also California [SB 1327] (2024, proposed)*

Efforts are being made to codify an expanded notion of what using the news in an online context might mean, beyond using direct quotations or an individual reading an article. Beginning in Australia, several laws and bills avoid the creation of new taxes or direct government involvement in payment by instead requiring negotiation (“bargaining”) or arbitration between publishers and platforms that carry news. The result is direct payment from platforms to businesses (though to date terms have been negotiated outside the mandatory framework).

Different from the Model 1’s copyright approach around content, the required negotiation agreements focus on the activity of “availability” or “access,” which encompasses the work that digital platforms undertake to acquire, crawl, or index information in order to make that information available online. In addition, this legislation tends to consider elements such as URLs and snippets of news articles as worthy of compensation (though existing copyright laws are meant to remain in place). In the New Zealand bill, making content available includes “when any part of the content is reproduced on the digital platform or when the digital platform facilitates access to the content by linking to it.”

All of these pieces of legislation define conditions through which bargaining, or ultimately arbitration, must take place between large platforms (e.g., Australia’s “significant bargaining power imbalance” or over 50 million users monthly in the case of JCPA) and news organizations, the definitions of which vary. Brazil’s effort, having been inspired by Australia’s Code, also focuses on the negotiation between news and technology companies.

In theory, this set of legislation leaves the precise terms of the remuneration to the negotiation, designed in part to allow for the possibility of collective negotiation. This exemption from antitrust enables news companies to organize. However, should a platform decide to no longer carry news, the requirement to negotiate may not be possible to enforce; in Australia, Meta has said it will drop news from its platform should the minister try to designate it under the Code. The law and its enactment can also be different, as the case with Canada has shown (discussed further in Model 4).

Model 3: Local Usage Fee around Link Distribution

Legal Mechanism: Platform payment for the local public’s direct access of journalism content, such as through clicks, or payment for locally relevant content

Financial Structure:

Journalism Defined/Protected As: Journalists, who are defined by employment time and tasks, within news organizations

Legislation with this model: United States – California [AB 886] (2024, not passed)*; United States – Illinois [SB 3591] (2024, proposed)

In contrast to the open-ended negotiating frameworks of Model 2, recent approaches in the United States have sought a more straightforward assessment or quantification of digital usage around distribution or links. Examples of payments to publishers based on the number of links can be found in two state bills, originally using virtually identical language: the California Journalism Preservation Act (AB 886), 2023 version and the Illinois Journalism Preservation Act (SB 3591), whose language copies much from the earlier California example.

Illinois’s proposal (which was very similar to California’s proposal prior to amendments to the CA bill on June 10, 2024) states that liable technology platforms must “track and record” the number of times an eligible journalism provider’s content is linked, presented or displayed to residents of the state on a given digital platform. The proposal further specifies how the usage fees will be allocated: one percent of the usage fee will go to “digital journalism providers that produce 30,000 annual search occurrences in Illinois searches or 10,000 annual social media impressions from Illinois.”

The bills using this funding mechanism have been criticized for possibly fueling clickbait and misinformation. Against these critiques, lawmakers revised California’s proposal in June 2024 in ways that deeply altered its structure as well as its language. Now instead of compensating for clicks, the bill attempted to outline strong reasons for online platforms to bargain with local news organizations – making it more similar to Model 2 in many ways. “Usage” was redefined as more generalized access to the content produced by journalists and the compensation model is much vaguer; the precise calculations evaporated from the California example. California’s latest version of the bill appears however to have been pulled off the table, in favor of a deal with Google and others that, among other elements, may provide newsrooms with nearly $250 million in support (a portion of this total is for an “AI Accelerator” which is not journalism specific).

Model 3 is noteworthy because these examples of legislation move away from defining journalism organizations alone and instead focusing on the professionals who work for them. The new version of California’s bill attempted to compensate news organizations with journalists — including freelancers — who produce information that is of relevance for “local California audiences,” though how that relevant access or usage will be measured outside of clicks was not clear.

The financial support in both of these bills (CA and IL) is structured to come from large digital platforms such as Google and Meta. Qualifying platforms are defined by their national user base (possessing 50 million United States-based monthly active users or subscribers) or national yearly revenue (550 billion USD in sales or adjusted market capitalization).

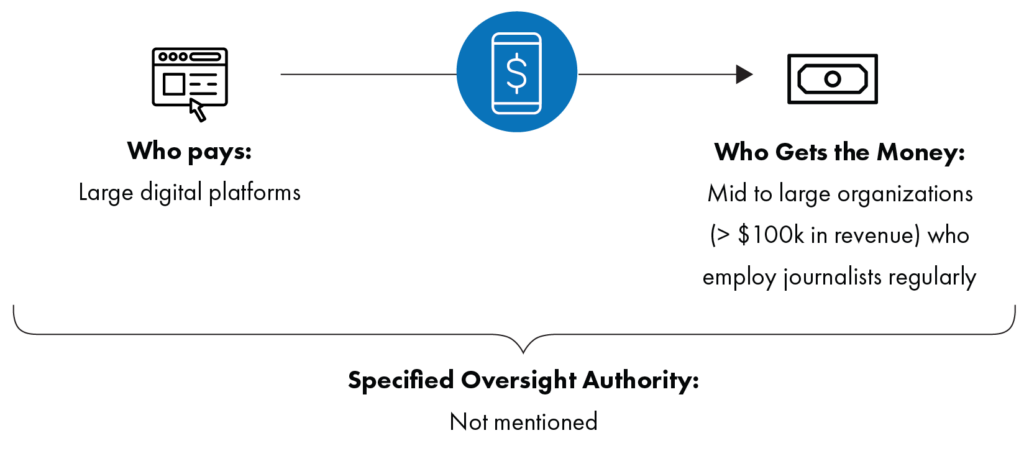

Model 4: Platform Support for News Organizations

Legal Mechanism: Platforms as financially responsible for a new digital environment in which the news industry cannot produce and distribute quality journalism

Financial Structure:

Journalism Defined/Protected As: Press organizations

Legislation with this model: Canada [C-18] (2023, enacted)*, Indonesia [Decree No. 191884] (2024, enacted)

Indonesia’s legislation states that digital platform companies have a responsibility to support “quality journalism” by cooperating with press organizations. Examples of collaboration between platforms and press companies include paid licensing and profit sharing. However, the regulation lacks specific details in several of the financial support provisions.

Inspired by the Australian News Media Bargaining Code (Model 2), Canada’s C-18 law did not initially involve the government serving a central role. However, the development of C-18 departed from Australia’s example in several ways. The implementation of C-18 led to a negotiation between Google and the Canadian government, rather than between companies. For this reason, Canada’s example now seems closer to requiring direct platform support of news organizations than the other legislation in Model 2. Meta, on the other hand, responded by removing all news organizations and links so that the law would not apply. Google threatened a similar removal of links prior to the negotiated agreement with the government.

It is unknown how these policies would fully work in practice. The Press Council in Indonesia, Dewan Pers, is a third-party industry association that is expected to have a large role in determining the outcomes and processes of how platforms support news companies in the country. As of July 2024, the Canadian Journalism Collective was still working out issues of governance with requirements for diverse representation among its directors.

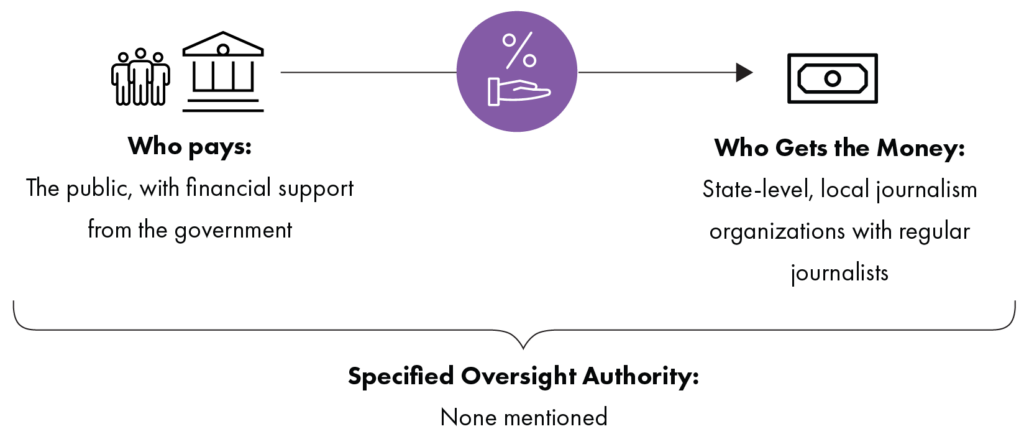

Model 5: Government Tax Credits

Legal Mechanism: Tax credits for local news, which citizens need access to

Financial Structure:

Journalism Defined/Protected As: Local for-profit newspapers, journalists

Legislation with this model: Canada [Canadian Journalism Labour Tax Credit; Digital News Subscription Tax Credit] (2019, enacted); United States – Virginia [HB 1217] (2022, not passed); United States [HR 4756] (2023, in progress); United States – Washington State [SB 5199] (2024, enacted); New York [A2958C] (2024, enacted); Wisconsin [AB 1140] (2024, not passed); Maryland [HB 540] (2023, in progress); Illinois [SB3592] (2024, enacted)*

This model exemplifies efforts to leverage tax credits as a way of supporting local news. Justification for the use of public monies for this purpose hinges on the importance of local news for citizens to be fully engaged in, and make decisions about, their communities.

Depending on the context, tax credits can be non-refundable, providing an exemption or “break” for qualifying businesses. They can also be refundable, potentially amounting to additional funding for particularly small organizations. Both types of credit can be seen in Canada, whose efforts became effective in 2019. The Canadian Journalism Labour Tax Credit offers a 25% refundable tax credit on salaries and wages while the Digital News Subscription Tax Credit offers all individuals a non-refundable personal tax break on subscriptions to qualifying organizations.

There are many ways that tax credits have been and are being considered. First, tax credits are being offered directly to journalism organizations. Examples include straightforward tax relief, as with the United States House of Representatives’s Community News and Small Business and Support Act (NSBSA), Virginia and Washington State. Examples from New York and Illinois offer refundable tax credits. New York’s law offers financial support to news organizations for the compensation (and retention) of journalists through tax credits, some percentage of which is refundable; It should be noted that the law benefits print newspapers explicitly, while non-profit, TV and radio organizations do not currently qualify. A similar situation exists in Washington State, where the emphasis is on print newspapers; local digital-only sites do not qualify.

Tax credits can also be considered for other companies, incentivizing advertising in local journalism. Maryland’s example focused on costs associated with advertising incurred by small to midsize newspapers. A similar effort is underway within the NSBSA and Massachusetts; Illinois recently passed a state budget that not only included $25 million of refundable tax credits for local journalist wages and funding for college scholarships (making Illinois’ case a hybrid with Model 6/government grants), but also tax credits for local businesses advertising in local newspapers.

Finally, tax credits can be offered directly to consumers themselves. Wisconsin initiated an effort to provide tax breaks to its residents for local newspaper subscriptions. In its current iteration, the bill did not pass the State Senate in April 2024.

Because this funding mechanism works within existing tax codes, no special oversight authority has been identified as required in either bill.

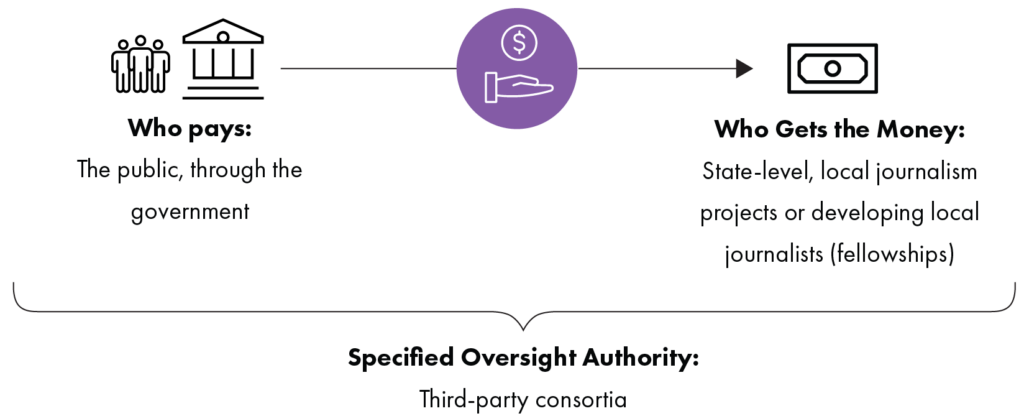

Model 6: Third-Party Government Grants

Legal Mechanism: Government support of local news through grants administered by third-parties, such as universities and consortia

Financial Structure:

Journalism Defined/Protected As: Local journalism efforts or developing journalists in local newsrooms

Legislation with this model: United States – New Jersey [A3628] (2018, enacted); Canada Local Journalism Initiative (2019, enacted); California [AB 179] (2022, enacted); New Mexico [SB 159] (2023, not passed); [SB 57] (2024, not passed) — though related governor-approved appropriations in both years; Wisconsin [AB 1139] (2024, not passed); Illinois [SB 3592] (2024, enacted); California [SB 1327] (2024, in progress – uncertain)

As opposed to Model 5 (tax credits), government grants actively give funding to more broadly defined journalistic efforts.

Because this model delegates decision-making to a consortium or other third parties, these laws do not include precise definitions of journalism content, organizations or individuals. This may allow grantors more creativity and flexibility in determining which efforts might benefit from funding. However, in cases where funding explicitly goes towards fellowships, it is clearly supporting workforce development within local newsrooms.

The amount of funding distributed through this mechanism depends on how much the governments designate. The level of funding can often be much lower than what is provided through the other models discussed in this report. As of 2024, the New Jersey Civic Information Coalition, founded in 2018 through State Bill A3628, has supported 81 projects with $5.5 million (USD) while Canada’s Local Journalism Initiative has given out $50 million (Canadian dollars) since 2019 and has recently committed $58.8 million more. California’s bill contained both types of financial support, with $25 million (USD) designated to the University of California at Berkeley to support local news fellowships and $5 million in grants for ethnic media.

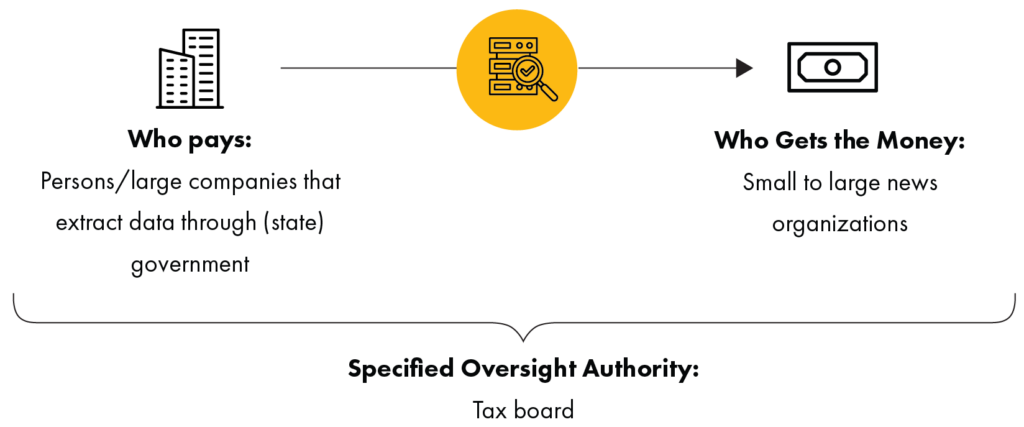

Model 7: Hazard Tax by Government upon Platforms

Legal Mechanism: Platforms extraction of (local) citizens’ data amounts to a general hazard that requires remuneration

Financial Structure:

Journalism Defined/Protected As: Local journalists/journalistic service providers

Legislation with this model: United States – California [SB 1327] (2024, in progress – uncertain)*

California has the only bill that fits within this model. This hazard tax (which has some significant distinctions in structure and operation than typical taxes — see the language of the bill for more) is supported by two justifications. The first is an understanding that large internet corporations are collecting data about people in order to advertise products and services to them. Because people exchange their data for access to the products and services, this “barter” is not captured within typical sales tax structures. The second is a recognition that journalism — especially ethnic media — performs a critical role in functioning, free societies. Implicit here is that advertising has been a critical part of journalism’s sustainability model (Section 1 of CA SB 1327).

Possibly due to these two purposes, there are two mechanisms for funding. Funding from large corporations would be obtained directly at the sales tax rate (7.25%), the results of which go into the “Data Extraction Mitigation Fee Fund.” This revenue eventually benefits qualifying journalism organizations after satisfying fundamental requirements such as school funding (Section 4). In addition, not only can qualifying organizations obtain credits against the taxes that they owe the state, but smaller organizations can also gain funding because it is structured as a refundable tax credit. Different from Model 5, tax relief is provided by the platforms so that there is no loss of revenue to the state. Furthermore, extra revenue paid by the platforms may directly fund organizations’ local news endeavors.

The bill’s author, Steve Glazer, likened his effort to taxes that mitigate environmental hazards. Though any internet corporation that employs the citizen data barter for targeted advertising might be held accountable, the bill only seeks remuneration from very large organizations; the amounts potentially owed by smaller technologies are regarded as “negligible.”

The legality of this effort is currently in question and may be challenged constitutionally based upon past decisions such as Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U.S. 233 (1936) and Minneapolis Star Tribune Company v. Commissioner, 460 U.S. 575 (1983). However, the recent negotiation among the State of California, Google and others that replaced the CJPA (Model 3) may also mean that Glazer’s bill will not move forward.

Part Two: Key Issues for a Sustainable Digital News Ecosystem

All legislative approaches under consideration attempt to address a critical requirement for the future of journalism: regular financing streams. They cannot and do not aspire to address all aspects of a sustainable digital news ecosystem. In fact, several of these measures have expiration dates or requirements for renewal, highlighting their stopgap or temporary approach to finding funding solutions for the news industry.

Yet laws can create long-lasting effects, which can only be mitigated through a thorough analysis of potential risks and tradeoffs. The justification for requiring payment from platform companies hinges on an emerging premise: the journalism industry, and with that the digital news ecosystem, may be sustained by charging for the digital “usage” of journalistic content by technology companies. Other approaches described in the models suggest that sustaining the news ecosystem may involve more compensation from governments.

Setting aside the ongoing debate about whether news providers can generate financial sustainability themselves, the following section discusses several issues related to the rationale behind the funding mechanisms. The first set focuses on the notion of compensation-worthy digital interactions beyond what a reader, consumer, or end user might also need to pay. The second set focuses on how these legislative examples handle the needs for diverse and independent journalism and journalism that serves the public.

The Concept of Digital Usage in Legislation

Across five of the models, the notion of usage encompasses the different ways that digital content is made available to the general public. Usage also applies to the technical means by which digital platforms process news information to make it available to a wider audience. For this version of usage, legislation such as Canada’s Act C-18 seek “fair compensation to the news businesses for the news content.”

“Use” and “usage.” Several pieces of legislation discuss the terms “use” and “usage” to describe different interactions with digital content.

- Examples from Models 1 and 2 focus on publications and content, particularly how they are made available via digital technologies:

- EU Directive (2019), Article 15 “Protection of press publications concerning online uses.”

- Brazil (2023): Section III-A; Article 21-A. “Journalistic content used by digital platforms for third-party content [Os conteúdos jornalísticos utilizados pelas plataformas digitais de conteúdos de terceiro] that have more than 2 million users in Brazil, produced in any format, including text, video, audio, or image, will result in compensation to the legal entities that produce journalistic content.”

- Examples from Model 3 focus on the sharing of that content through links:

- California (2023 version): “journalism usage fees”; “journalism usage fee payment.”

- California (2024 version): “Title 23. Compensation for Journalism Usage.”

- Illinois (2024): “Section 15. Notice requirements for journalism usage fee payments.”

- Model 7 focuses on digital use through the data collected by end users or news consumers.

“Access” and “availability.” Though examples from Models 2 and 4 do not always employ the explicit term “usage,” their descriptions of digital “access” or “availability” mimic the kinds of interaction captured in the other models.

- The Australian and Canadian examples employ the terms availability, as well as interaction and (in Australia) distribution.

- In the US JCPA, “use” may be distinct from “access.” The term is tied to a series of activities that are not the subject of the bill (e.g., “no antitrust immunity shall apply to … the use, display, promotion, ranking…”).

- New Zealand’s Bill (2023) employs both the terms “availability” and “use”: “Supporting the efforts of New Zealand news media entities to secure revenue for the use of their content online will provide a critical revenue stream and mean that the sector will not be reliant on government funding in the future.”

It is also worth noting that while this legislation and this report center on revenue lifelines for journalism, questions around fair compensation and usage are also at the heart of other policy discussions related to journalism and technology, such as the use of content to train generative AI models.

Issue: When Is It Appropriate to Charge for Digital Usage?

Exactly what digital usage of news information warrants compensation? Significant portions of journalism’s content are now being distributed through digital platforms which offer far less industry control than earlier distribution methods like print. Recent legislation reflects various ways lawmakers are addressing the question of compensation for digital usage.

Much of this legislation aims to overturn common understandings and practices on the internet that — due to the protections of open knowledge and public exchange in many democratic societies — allowed many aspects of an article’s content, such as its URL, title and short summaries, to be referenced, shared, accessed or “used” without compensation. This is because ideas, information and facts are not copyrightable. Thus, there are questions that need to be addressed in order to isolate whether the concept of appropriate compensation around digital usage can support journalism moving forward and, if so, how.

Usage or Discovery: Determining Link Value. As researchers and others seek to quantify the significance of technology platforms providing access to news, there is a critical question at hand: What precisely is the value of facilitating digital interactions by linking to news? Is it usage, discovery or both? Much remains unclear.

- The News Media Alliance and Initiative for Policy Dialogue argue that large platform technologies such as Google and Meta gain significant financial benefits from the inclusion of news information. On the other hand, Meta’s decision to remove news from its platform in Canada and to consider removing news from the Australian market suggests that the financial gains may not be significant.

- Others argue that providing access is a promotional service to news organizations — like a newsstand or grocery aisle with publications — allowing their content to be discovered; sharing information via aggregators may draw people to news content more. In fact, a recent study has shown that the majority of Canadians appear not to notice that they have lost professional news content — not only are they not visiting traditional or ethically-minded news sites, they are now using the platform to get a more biased and less-factual kind of news.

- The recognition that technology platforms provide valuable traffic to news organization content has led to the inclusion of non-retaliation clauses within many agreements so that platform companies do not willfully affect that traffic. However, non-retaliation agreements may suggest that, in order to ensure the appearance of compliance with the law, technology companies are now required to carry all news providers. The requirement to carry news content may fundamentally change the purpose of certain digital products. It may also negate the concept of fair compensation for digital usage altogether if a technology has no choice but to provide it. There is some debate on this issue.

- If “usage” equals “the digital processing of content,” what constitutes digital processing varies depending on the result or product. In some instances, small elements of metadata allow for discovery of news information without computation. But, other kinds of digital interactions for various news products (e.g., automatic news summaries) likely require more processing of the original text or content. With the incorporation of generative AI, how we define “computational usage” is also important.

Diminishment of Open News, Expansion of Copyright? Charging for digital usage expands copyright and producer or author rights in ways that raise questions about the open sharing of news in a digital context. Compensation for digital usage may also be illegal in certain contexts.

- The question of whether “access” qualifies as compensation-worthy usage poses a problem for a context like the United States where the “fair use” of information exists. Fair use is a way that copyright-protected works can be used without compensation in certain contexts that protect the public’s freedom of expression and incentivizes creativity in a way that benefits society.

- Moreover, within the United States, legislation that impinges on the curation or moderation of third-party content is eligible for First Amendment protection; the Supreme Court’s recent Moody v. NetChoice (2024) decision rejected any must-carry obligations.

- In contexts where author rights exist, such as the EU and Brazil, we see the actual or potential removal of exemptions for news content. Take, for example, the Copyright and Information Society Directive 2001 (2001/29/EC), which was amended by the 2019 Directive reviewed in this analysis. The Copyright and Information Society Directive used to explicitly provide for exceptions and limitations to copyright in EU states when it came to making news available (Section 5).

- Either way, the information and facts of news reports themselves are not copyrightable. This makes the effort to define compensation around digital interactions particularly thorny. Exceptions to copyright and author protections are also made in the name of education and scientific progress. This may also be why a key metric in the EU Directive regarding digital interactions with news content has to do with time (2-year expiration). Despite efforts to limit their impact, there is a risk that the expansion of these rights lessens incentives to use up-to-date information.

Impact on Paywalls. If consensus about fair compensation for digital usage is achieved, should this have an impact upon content paywalls? For example, if local news organizations gain tax breaks or subsidies from the government — which ultimately come from taxpayers — does this require some of that news to be freely accessible to the public?

Issue: Is Compensation for Digital Usage Consistently Applied?

Beyond any questions regarding the principle itself, there is still no clear consensus as to how compensation for digital usage is applied either when considering which elements of digital content qualify or how to calculate the compensation. This lack of consensus is an indication of the difficulties behind the overall concept of compensation for digital usage.

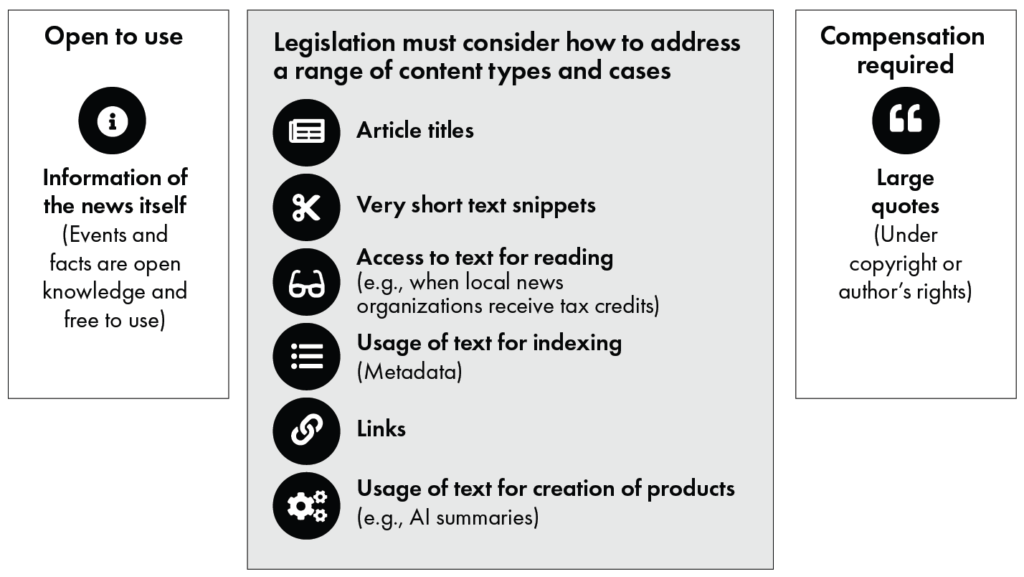

Variance in Applicable Components. A number of components in news content — such as URLs/ links and quotes — are being directly addressed or indirectly referenced by this body of legislation. However, the different pieces of legislation do not always agree with each other about the treatment of these specific elements.

- The EU Directive does not require compensation for the use of internet addresses such as links/URLs or brief texts (sometimes called “snippets”) in contrast to the Australian Media Bargaining Code which does. Furthermore, among EU Countries, there is some disagreement about what exactly qualifies as “very short text” versus a “snippet.” In the case of the required negotiation agreements described in Model 2, “access” itself to journalistic products is considered enough of a warrant to require remuneration.

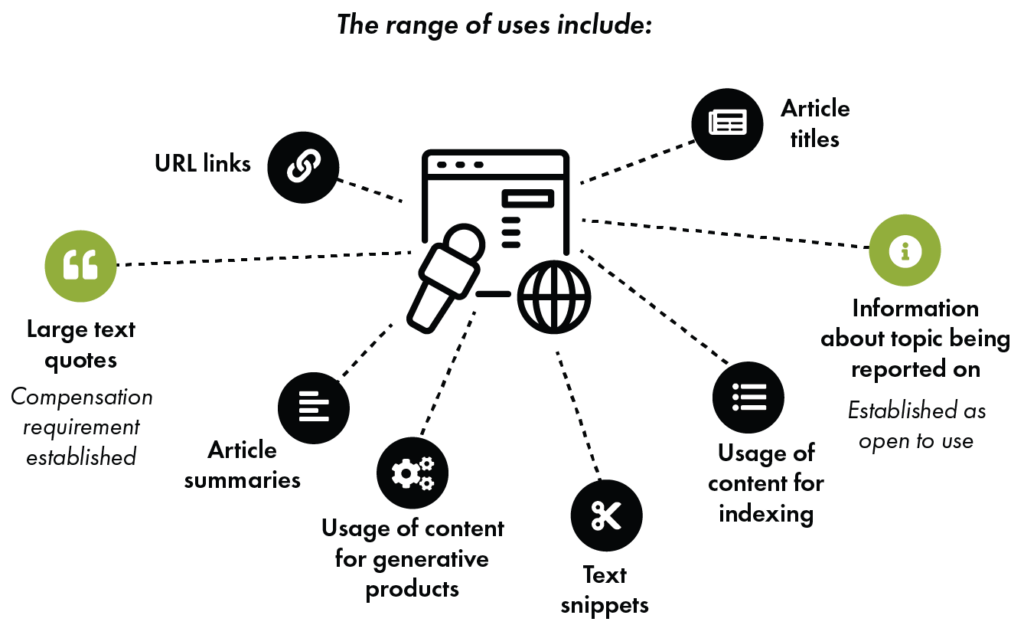

- Digital usage components directly or indirectly addressed in the legislation that may or may not call for compensation include:

- URL links

- Article titles

- Very short texts and text snippets

- Larger text quotes

- Article summaries

- Usage of text and audiovisuals for indexing

- Usage of text and audiovisuals for generative products

- Information about the event or fact being reported on

Inconsistent and Limited Application. Compounding the lack of clarity around which elements of news content justify compensation, there are also inconsistencies in application. Though usage is defined, the formulas for compensation vary and it is not being applied to every organization or entity who might qualify. These inconsistencies undermine the usage argument.

- For example, there is an inconsistency in the metrics and definitions of usage rate: while some laws focus on the amount of content being used as a way to create the formula for compensation (Models 1 and 3), others look at the news costs for an organization, no matter how much content it may generate (Model 5). The formula is not always transparent, as with Australia’s agreements which are confidential (Model 2).

- There is a risk that sensationalist and malign reporting could be remunerated in some cases. In Australia (Model 2), there are ethics tests that news organizations must undergo to prevent the funding of sites that do not engage in editorial review or fact-checking. However, this type of review does not exist across the board (e.g., the controversies around the earlier version of California’s AB 886).

- Most of these proposed statutes also focus on defining applicable usage fees for a specific group — only very large platforms qualify (such as platforms with at least 50 million impressions per month or “third-party digital content platforms that have more than 2 million users”). These efforts are an attempt to rebalance the flow of digital revenue away from the companies earning significant monies from advertising. While the focus on larger companies may provide access to larger sums of money, it does not fully define what is worthy of compensation regardless of the user. For example, should news organizations themselves — many of whom have also created technology platforms for themselves that share external links — fall under this “appropriate compensation” concept?

What content is free and what deserves compensation?

Issue: Who Benefits from Appropriate Compensation?

While this body of legislation makes the argument that digital usage warrants compensation, it is not yet clear what exactly that compensation should amount to or who should benefit from it. The financial mechanisms included in many examples of legislation could apply to all content being aggregated and re-distributed on the internet. There is also the question of whether the results of these mechanisms are fair to the public.

Within these financial mechanisms, there are inconsistencies and limits to who may qualify. The various legislative efforts approach the challenge of identifying and protecting legitimate beneficiaries differently, whether based on content, organization, professionals or some combination. With the intended goal of bolstering news sustainability, further consideration is warranted about who is covered and how news organizations may use the funds they receive.

Journalistic Content. Journalism topics, information or publication formats included within the legislation focus on current affairs and the public interest.

- The main orientation of Model 1, expanded copyright, is around the content. As such, the EU Directive does not include a definition for journalism or journalist, though it does include a definition for press publication. Compensation in Brazil’s example must take into account the amount of original journalistic content created, among other factors. Laws and bills from Model 2 tend to focus on the notion of news content dealing with current affairs and the public interest, with beneficiaries defined as the organizations (e.g., producers, broadcasters, businesses, entities, etc.) who produce this content.

Journalism Organizations. The journalism organizations (i.e., organizations that produce journalism or who employ journalists) protected by the legislation tend to be online, traditional and midsize or large, though there are sometimes explicit protections for small, local outlets especially in government-supported mechanisms.

- In Models 2 and 3, pieces of legislation are expressly focused on midsize or larger organizations. For example, qualifying organizations are based on thresholds for revenue which include $150,000 (AUD) in Australia and $100,000 (USD) in the US (though the 3 largest US publishers are excluded from JCPA). An important question is whether hedge funds, which own news organizations, may qualify.

- For those in Australia and New Zealand (Model 2), organizational qualification checks include professional standards tests, audience tests and content tests. The legislation in Australia and New Zealand do not require any transparency about how the funds within an organization should be spent while the legislation crafted by the US (Model 3) and Canada (Models 2 and 4) added a transparency requirement.

- Under Model 5, Wisconsin’s attempt provides subscription credits to local news organizations, however, New York’s effort excludes consideration of non-profit and broadcast entities.

Journalists. Qualifying journalists are mostly defined by full-time work within a range of specific kinds of tasks within formally incorporated news organizations, though some legislation recognizes freelance roles.

- Perhaps in growing recognition that earlier legislative attempts may not support the actual production of news, Model 3 focuses on trying to ensure that journalists are themselves beneficiaries. Journalists are defined as humans or “natural person(s)” who engage in a number of news production activities such as “gathering, preparing… presenting, distributing, or publishing original news or information…” (AB 886) (though it is not entirely clear what type of original news gathering could qualify). Organizations then become qualified if they, for example, spend 50%-70% of the received revenue on journalists. The most recent revision to California’s bill also made sure to include freelance journalists.

- In Model 4, Indonesia’s regulation stipulates that “news is a journalistic work by journalists” in a context where journalists have official press cards.

- In the New York example from Model 5, a qualifying news journalist resides within 50 miles of the local news agency under consideration for the tax credit and must work at least 30 hours per week on qualified services (i.e., activities related to producing original news content). Model 7 focuses on outlining requirements such as the residence of full-time journalists, who are defined by activities such as “gathering, preparing, recording, directing the recording of, producing, collecting, photographing, writing, editing, reporting, presenting, or publishing original local community news for dissemination to the local community.”

| Type | Protected Journalism |

|---|---|

|

Model 1: Ancillary Copyright around Content

|

Certain types of copyrighted content or copyrighted publication in any form; hyperlinks are exempted |

|

Model 2: Required Negotiation with Businesses

|

Content or publication/organizations (US: journalist) |

|

Model 3: Local Usage Fee around Link Distribution

|

Journalists, who are defined by employment time and tasks, within news organizations |

|

Model 4: Platform Support for News Organizations

|

News organizations |

|

Model 5: Government Tax Credits

|

Local for-profit newspapers, journalists |

|

Model 6: Third-Party Government Grants

|

Still to be clarified, but local journalism efforts |

|

Model 7: Hazard Tax by Government upon Platforms

|

Local journalists/journalistic service providers |

Balancing Financial Streams with Core Elements of Journalism

Beyond the issues related to digital usage and compensation, we turn our attention to the main goal of the legislation: sustaining journalism so that it can ultimately fulfill its mission to support functioning, free societies. In finance-focused approaches, it is important to examine what might be missing and what might unintentionally introduce new risk to advancing this overarching goal.

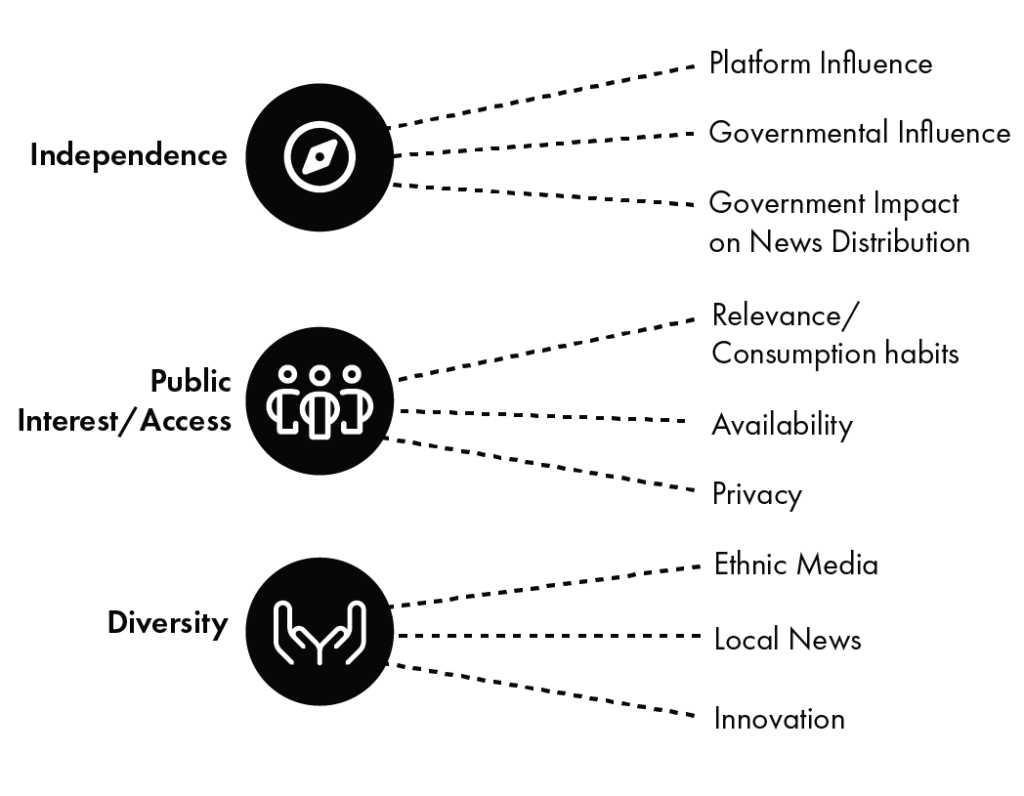

A range of values and ethical considerations are important for strong, high quality journalism. Particularly in today’s digital world, CNTI has laid out five components critical to a fully sustainable digital news environment: revenue to support journalistic work; journalistic independence; diversity of providers; technology to produce, distribute and receive news; and a public that finds journalism valuable and relevant.

This analysis considers three of those elements beyond revenue: (1) diversity, (2) independence from influence and conflicts of interest and (3) public service (including what is relevant to the public). A detailed examination of the language inside each piece of legislation related to these three elements can be found in this table.

Issue: How Can We Sustain Diverse Journalism?

One of the ways the internet has proved transformative for news is how it has diversified both the forms and producers of journalism. With Web 2.0, the world read, heard and engaged with many different perspectives on a range of topics, some of which had never received attention in mass media. As Canada’s efforts have noted, “citizens’ access and exposure to a diversity of content play a central role in the making of a resilient democracy.”

Within the legislation, we find little overall attention to journalistic diversity. The safeguarding of diversity includes aspects of journalism’s content, organizations and its professionals, as well as dimensions such as ethnic media, those serving gender identity or other special communities and independent and freelance journalism. We selected a few to consider here.

Minority Ethnic Media. Some special considerations exist for minority ethnic media; however, it is not always clear whether and how these outlets will receive funds.

- Two of the examples from Model 2 consider contributions from minority media. Both Canada and New Zealand’s legislation also feature specific provisions for indigenous (Canada) and Māori (New Zealand) news media. These special protections for diverse news are not found in the Australian or United States legislation. While these protections are valuable, they miss opportunities for a more comprehensive consideration of what supporting minority media might entail. However, the administrators over Canada’s Local Journalism Initiative, mentioned in Model 6, may allow for more comprehensive consideration.

- Both the California and Illinois legislative drafts from Model 3 cite minority ethnic and, in particular, Black media’s importance: “Given the important role of ethnic media, it is critical to advance state policy that ensures their publishers are justly compensated for the content they create and distribute.”

- Yet, it is not clear that especially small minority publications, though mentioned in the preamble of the California’s draft, would be rewarded. A number of small, local ethnic media do not meet the thresholds of revenue. As print publications, minority ethnic outlets also may not qualify since these legislative efforts are focused on digital distribution.

Local Journalism. Several of the models make reference to local news, with some examples of legislation specifically striving to protect local journalism organizations and the journalists who work within them. However, locality is a relative term, and is defined differently in the pieces of legislation that reference it. It would be helpful to consider the concept and language more thoroughly.

- Models 2 and 3 make reference to local news, but have no special provisions other than national or state-level registrations or physical locations.

- Models 5 and 6 focus on local organizations with local journalists, as described earlier, such as New York’s journalist residency requirement.

- Model 6 also offers examples where grants and fellowships through universities or other organizations can support local journalism projects.

- The aim of the California bill in Model 7 is to support local journalism, which mentions the consideration of small ethnic outlets. Local journalism is determined by the residence of full-time journalists who are defined by activities such as “gathering, preparing, recording, directing the recording of, producing, collecting, photographing, writing, editing, reporting, presenting, or publishing original local community news for dissemination to the local community.” Smaller outlets receive a larger percentage of funding relative to their size.

Innovation. While we can see some areas in which news diversity is being considered or protected, this is not the same as creating a context in which journalism might flourish. The stated goal of much of this legislation is triage: to simply give journalism a financial lifeline. Thus, the legislation overall does not consider the issue of continued developments within journalism or what might be required to remain flexible in the future.

- The EU Directive within Model 1 and the New Jersey Consortium of Model 6 are the only examples within our analysis that approach the challenge of providing additional revenue while considering creativity and continued innovation in the digital marketplace. For example, the Directive notes that a “harmonised” legal framework needs to protect against the exploitation of works, thereby “stimulat[ing] innovation, creativity, investment, and protection of new content” while also allowing for limitations to education and also, potentially, text and data mining technologies.

- Copyright can aim, it has been argued, to protect diversity and robustness in journalism by rewarding the creativity of all outlets, including small ones, because it applies to all content rather than a particular type of provider. Whether ancillary copyright proposals further or diminish this diversity is a point of discussion.

Issue: How Can We Sustain Independent Journalism?

Independence from influence and conflicts of interest have long been a key value and ethical consideration in journalism. For some, usage payments from technology companies to journalism providers alleviate concerns about the dependence of the journalism industry on digital platform companies (such as to reach audiences or philanthropic offerings of money or technology tools). The creation of mechanisms that justify fair or reasonable compensation by technology companies may help to do this, but they require laws.

With increased legislation, there are increased implications for governmental influence — especially long-term as government regimes change. Indeed, as CNTI discusses in other publications, press freedoms around the world are in decline across all government regime types, alongside increased government reach. We also explore possibilities where legislation may inadvertently increase dependence upon technology companies.

Government Influence in Financial Determination. When it comes to the implementation of these different pieces of legislation, questions arise as to when and how special bodies will exercise their oversight and whether they have a role in determining who receives compensation.

- Some of the legislation within Models 1, 3 and 5 do not outline special roles for government, relying instead upon the existing structures of courts for copyright and tax commissions for tax credits. However, there is governmental involvement in defining which organizations or individuals can qualify for tax credits to begin with.

- Other legislation within Models 2 and 7 outline special roles for governmental agencies and regulators. These duties include designating companies who must negotiate, validating the eligibility of news organizations and enabling arbitration in negotiations with technology companies. Sometimes governmental involvement may be limited to refereeing arbitration. As currently worded, Brazil’s draft legislation includes details about the institutions responsible for overseeing fair negotiations (e.g., a Private Chamber of Arbitration or a body of the federal government (Article 21-A para. 9)).

- Uncertainty exists regarding precisely how these pieces of legislation will be implemented in many instances. Though we know that the extra-governmental Press Council has been identified as the body of special oversight in Indonesia under Model 4, the details of this role have not yet been determined. And under Model 7, the California Franchise Tax Board suggests that certain organizations, such as ethnic media or smaller outlets, may gain priority in funding but it is as yet unclear how this will be determined.

Government Impact on News Distribution. The current legislative examples tend to increase the likelihood that news distribution will be affected.

- Some legislation under Model 2 may include requirements for platforms to carry all purported news organizations indiscriminately, albeit that requirement may be unintentional. The “non-retaliation” stipulations within the required negotiation agreements are intended to ensure that platform companies do not attempt to take actions against organizations who wish to use the mechanism. However, as discussed earlier, platforms may consider themselves required to carry the content of all providers that identify themselves as news outlets, including propaganda or promotional sites, in order to not fall afoul of this law. This stipulation may now be unconstitutional in the United States after the Moody v. NetChoice decision.

- In Model 4, Indonesia’s case is still undetermined, but seems to require platforms to enforce potential Press Council directives. Overall, much is still unknown about how Indonesia’s policy would work in practice. While the Press Council has been an important function of journalistic independence from the government, there is also evidence that its authority can be sidestepped.

Platform Influence on Journalistic Content and Funding. While this legislation seeks to empower news organizations through increased bottom lines, and offers increased opportunities for non-philanthropic funding from technology platforms, questions of platform independence, let alone greater dependence, still exist.

- In several of the models, it seems that platform influence may now be introduced in different ways. News companies are dependent upon technology companies to provide them a digital definition of locality in Models 3 and 6. In other examples, the legislation or implementation is simply unclear.

- Increasing the percentage of funds coming from technology companies can make a news organization literally dependent upon those companies, raising questions about possible downstream effects to that organization’s editorial decisions or other issues.

Issue: How Can We Sustain Journalism that Serves the Public?

A central need for functioning, free societies is an informed, engaged public. Thus, so is news that serves the public and a digital news environment that is openly accessible to them. The models of legislation in this analysis vary in how well they support these goals. While some references are made to serve the public interest, what that actually means or how these pieces of legislation do that is either vague or omitted. The legislative efforts also often neglect issues such as privacy or the risk of losing access to news in online platforms altogether.

The Public Interest (or Interests). When invoked, the meaning of the term “the public interest” is not always clear — it is sometimes “The Public Interest” in terms of the common welfare, but it at times is about topics the public is interested in or curious about.

- On the one hand, the goal of supporting journalism that serves “local, regional, national, or international matters of public interest” is explicitly addressed in a couple of the models, particularly in Model 2. In the Australia example it is clear this includes what Australians consider to be important: “current issues or events of public significance for Australians at a local, regional or national level” or “issues or events that are relevant in engaging Australians in public debate and in informing democratic decision-making.” This attempt to define the content worthy of legislative support makes sense, but what if deep entertainment-related news is, in fact, what a certain portion of the public relies upon?

- On the other hand, the New Zealand proposal does include broader categories for relevant news content such as “communities that share other characteristics (including age, disability, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, ethical belief, or religious belief); or (e) people with an interest in specific subject matters (including the arts, sports, science, health, business, or the environment).”

The Public’s Privacy. The issue of what is owed to the public when it reads news and when its data is used (or “extracted” in the term of the most recent California bill) is a question that not only platforms but also news organizations should answer.

- For a different consideration of what might be in the public interest, we note a potential issue around citizen privacy within Models 3 and 6 — in measuring what California/Illinois citizens read, there is the small potential that tracking or collecting data about what citizens are doing (at the IP level presumably) would be in collaboration with a governmental agency.

The Public’s Access. Here we focus on the public’s literal accessibility so that one can digest key information that is relevant to know in free societies, particularly within democracies. Making journalism widely accessible is another area largely improved with the birth of the web and online distribution. Will legislation seeking to bring a lifeline to journalism providers inadvertently make it harder for people to access news they find relevant?

- Depending on how the laws are implemented, an unintended effect of ancillary copyright in Models 1-3 may be a reduction in access to information that is in fact fair to use within the United States. For the EU, more research is needed to determine whether the 2-year embargoing of content has in fact resulted in less availability of journalistic content. At the same time, in the face of carry requirements, large platform companies have removed news from their technologies altogether as is currently the case with Meta in Canada.

- Through the provision of tax credits, Model 5 creates a way in which local journalism organizations can gain some indirect or direct compensation for their efforts. One fiscal estimate for Wisconsin’s AB 1140 found that the state could lose around 30.8 million USD in revenue per year as a result of tax credits for newspaper subscriptions. Though news organizations would be supported by tax dollars, what has not yet been discussed is at what threshold this support will result in increased public access to their content.

How Legislation Addresses Journalistic Principles

CONCLUSION

Our analysis only takes a sample of remuneration efforts to consider how, in this moment of industry crisis, legislation may affect the long-term future of our digital news ecosystem. We know that we need many ways forward since not a single revenue source, law or other effort will be able to do everything when it comes to sustaining journalism.

The digital transformation has not just created a crisis for the industry, but also led to transformations within news. The definitions of who produces news and journalism are changing as well, and they may not necessarily be traditionally trained and professionalized individuals, let alone organizations. CNTI is exploring these very questions in a series of public and journalist surveys. New types of journalism creators are just one example of what is not captured yet in legislation.

What is encouraging about the recent legislative activity is that it shows the high level of effort, worldwide, that many are willing to undertake in an effort to sustain journalism. So, as legislation is developed, how can we make sure that it sustains the kind of journalism and information environment that we want, or that are needed for functioning, free societies?

Through our distilling of recent legislation into seven financing models, several areas for further consideration emerge. Summarized here, and discussed more thoroughly in the overview, they are:

- Reviewing recent financial models around the world brings to light the serious questions at hand about what a sustainable news media means and what it will look like in the years to come.

- It is important to address parameters around the use and sharing of digital content, but the way this legislation has begun to define it is problematic.

- A healthy news ecosystem requires a diversity of journalistic orientations, styles and innovations to serve the full public. Protection and further advancement in this area deserves top-level attention in legislative deliberations.

- This legislation as a whole raises questions about journalistic independence which should be directly addressed, especially in a global environment of declining revenue and press freedoms.

- These legislative efforts do not fully consider how to serve the public, including how the public stays informed and the kinds of journalism it values.

- The evolution of media remuneration legislation has brought some improvements, but both journalism and the public can be better served if those involved in discussions more thoroughly and proactively evaluate the legislative options.

Amid these areas that we deem worthy of closer consideration, the question then becomes what are the most effective legislative approaches, according to context. While a large part of that is what will hopefully come out of collaborative discussions that CNTI plans to help convene, a few guideposts emerge from this analysis:

Next Steps:

- First and foremost is to take a more deliberative and comprehensive approach to the legal path being paved around the digital use of and access to content. This includes parameters around what (and to whom) compensation is justified and how this applies to the wide range of actors, various types of content, diverse styles of usage as well varied levels of content moderation globally.

- Second is to try and fully consider how action addressing one critical element of a sustainable news environment impacts other elements. It is unlikely that any single piece of legislation can accomplish what is required to achieve a sustainable news ecosystem, so we must consider what combination of policies and laws may need to advance simultaneously in order to create the strongest mix of safeguards possible.

- Third is to apply a comparative analysis of legal definitions and the obligations of journalism to other journalism-related policies, including those developing around the use of Artificial Intelligence. These conclusions reflect recent legislation focused on remuneration of journalism, but in developing policies to address any one specific issue, it is critically important to explore the effects of those policies holistically.

Especially as legislation continues to be developed and implemented, we urge more conversation to advance the points raised above. In addition, research will continue to be critical in keeping track of these concerns as well as questions about how to sustain journalism and the ecosystem to which it belongs. Throughout, keeping note of the definitions of journalism — its content, organizations, professionals and the information environment in which it operates — will be fundamental to developing effective policy.

References and Resources

Bills Included in This Report

The bills/laws included in this report are included below by their most recent update (as of August 2024):

- Australia [Act No. 21], “News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code” (March 2021)

- Brazil [PL 2370], “Copyright Law Reform” (August 2023)

- Canada [C-18], “Online News Act” (June 2023)

- European Union [2019/790], “Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market” (April 2019)

- Indonesia [Decree No. 191884], “Presidential Regulation on Publishers’ Rights” (February 2024)

- New Zealand [GB 278-1], “Fair Digital News Bargaining Bill” (August 2023)

- United States [HR 4756], “Community News and Small Business Support Act” (July 2023)

- United States [S. 1094], “Journalism Competition and Preservation Act” (July 2023)

- United States – California [AB 179], “Budget Act of 2022” (September 2022)

- United States – California [AB 886], “California Journalism Preservation Act” (July 2023)

- United States – California [SB 1327], “Income Taxation: Credits: Local News Media: Data Extraction Transactions” (May 2024)

- United States – Illinois [SB 3591], “Journalism Preservation Act” (May 2024)

- United States – Illinois [SB 3592], “Strengthening Community Media Act” (August 2024)

- United States – Massachusetts [H. 2958], “Local Community Newspaper Tax Credit” (August 2024)

- United States – Maryland [HB 540], “Income Tax – Local Advertisement Tax Credit” (February 2023)

- United States – New Jersey [A3628], “New Jersey Civic Information Consortium” (August 2018)

- United States – New Mexico [SB 159], “Local News Fellowship” (February 2023)

- United States – New Mexico [SB 57], “Local News Fellowship Program” (January 2024)

- United States – New York [A2958C], “Local Journalism Sustainability Act” (April 2024)

- United States – Virginia [HB 1217], “Virginia Local Journalism Sustainability Credits” (February 2022)

- United States – Washington [SB 5199], “Providing Tax Relief for Newspaper Publishers” (January 2024)

- United States – Wisconsin [AB 1139], “Civic Information Consortium Board” (April 2024)

- United States – Wisconsin [AB 1140], “Local Newspaper Subscription Credit” (April 2024)

- We note that in Brazil, The National Federation of Journalists proposed to create a tax on ad-revenue in order to create a national independent fund to support journalism (in a format inspired by the Cinema National Fund). Source: https://fenaj.org.br/fenaj-defende-propostas-de-cide-e-fundo-publico-para-o-jornalismo-em-evento-do-cgi-br/

References

Abernathy, Penelope Muse and Sarah Stonbely. “The State of Local News: The 2023 Report.” Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern. https://localnewsinitiative.northwestern.edu/projects/state-of-local-news/2023/

Aiello, Rachel. “‘No Concessions’ St-Onge Says in $100M a Year News Deal with Google.” CTV News, November 29, 2023. https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/no-concessions-st-onge-says-in-100m-a-year-news-deal-with-google-1.6665565.

Basu, Brishti. “Federal Money’s Kept Hundreds of Journalists Employed in Canada. But the Program’s Set to Expire.” CBC, February 16, 2024. https://www.cbc.ca/news/federal-funding-journalists-expire-1.7116950.

Bennett, Tess. “Meta Threatens Australian News Ban in Media Bargaining War.” The Australian Financial Review, June 28, 2024. https://www.afr.com/technology/meta-threatens-australian-news-ban-in-media-bargaining-war-20240628-p5jpjc.

Buni, Catherine. “4 Ways to Fund — and Save — Local Journalism.” Nieman Reports, May 7, 2020. https://niemanreports.org/articles/4-ways-to-fund-and-save-journalism/.

Campbell, Jon. “New York’s $90M Tax Break for Local News Outlets Leaves out TV and Nonprofits.” Gothamist, May 16, 2024. https://gothamist.com/news/new-yorks-90m-tax-break-for-local-news-outlets-leaves-out-tv-and-nonprofits.

Caruth, Bradley. “Fiscal Estimate – 2023 Session.” Wisconsin Department of Administration, March 6, 2024. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2023/related/fe/ab1140/ab1140_dor.pdf.

Center for News, Technology & Innovation. “Building News Economic Sustainability,” July 23, 2024. https://cnti.org/article/building-news-sustainability/.

Center for News, Technology & Innovation. “Defining AI in News,” April 5, 2024. https://cnti.org/article/defining-ai-in-news/.

Center for News, Technology & Innovation. “World Press Freedom Scores Fall Back to 1993 Levels – the Launch Year of World Press Freedom Day,” May 3, 2024. https://cnti.org/article/world-press-freedom-scores-fall-back-to-1993-levels-the-launch-year-of-world-press-freedom-day/.

Chiou, Lesley, and Catherine Tucker. “Content Aggregation by Platforms: The Case of the News Media.” MIT Sloan Research Paper 6925, no. 23 (January 6, 2017). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4373444.

Clark, Tom. “California Journalism Preservation Act.” Assembly Bill Policy Committee Analysis. California General Assembly, May 2, 2023. https://trackbill.com/s3/bills/CA/2023/AB/886/analyses/assembly-judiciary.pdf.

Connal, Sulina. “Google Licenses Content from News Publishers under the EU Copyright Directive.” Google, June 15, 2023. https://blog.google/around-the-globe/google-europe/google-licenses-content-from-news-publishers-under-the-eu-copyright-directive/.

Dear, Jeremy. “Fixing a Global News Problem.” Columbia Journalism Review, February 27, 2023. https://www.cjr.org/special_report/disrupting-journalism-how-platforms-have-upended-the-news-part-7.php.

Delbyck, Kyle. “Press Freedom Is under Attack in Indonesia.” Al Jazeera, August 13, 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2022/8/13/press-freedom-is-under-attack-in-indonesia.