Definitions: Journalists Easily Articulate Their Distinct Role in Society but Do Not Think the Public Can

Definitions: Journalists Easily Articulate Their Distinct Role in Society but Do Not Think the Public Can

There is no consensus definition of journalism, at least in part by design. Thirty years ago, examining a definition did not seem necessary. People could rely on obvious physical traits: the broadsheet newspaper and the 30-minute newscast, for example, which were almost exclusively produced by professional and institutional outlets.

But as the media universe expands, it has become harder to easily differentiate journalism from other content. Social media feeds have largely standardized the way external links look and feel, and the wide availability of high-quality web templates has also blurred once-reliable visual cues. Furthermore, many more people are now involved in the process of getting informed by posting eye-witness accounts, sharing news stories digitally and offering commentary and analysis about the day’s events. At the same time, governments are increasingly defining journalism in policy, both in actions to support journalism and to suppress it. These shifts have made it more important to consider definitions of journalism.

CNTI has been exploring the changing definition of journalism through the Defining News Initiative which includes surveys and focus groups with the public, policy analyses and now this survey of journalists.

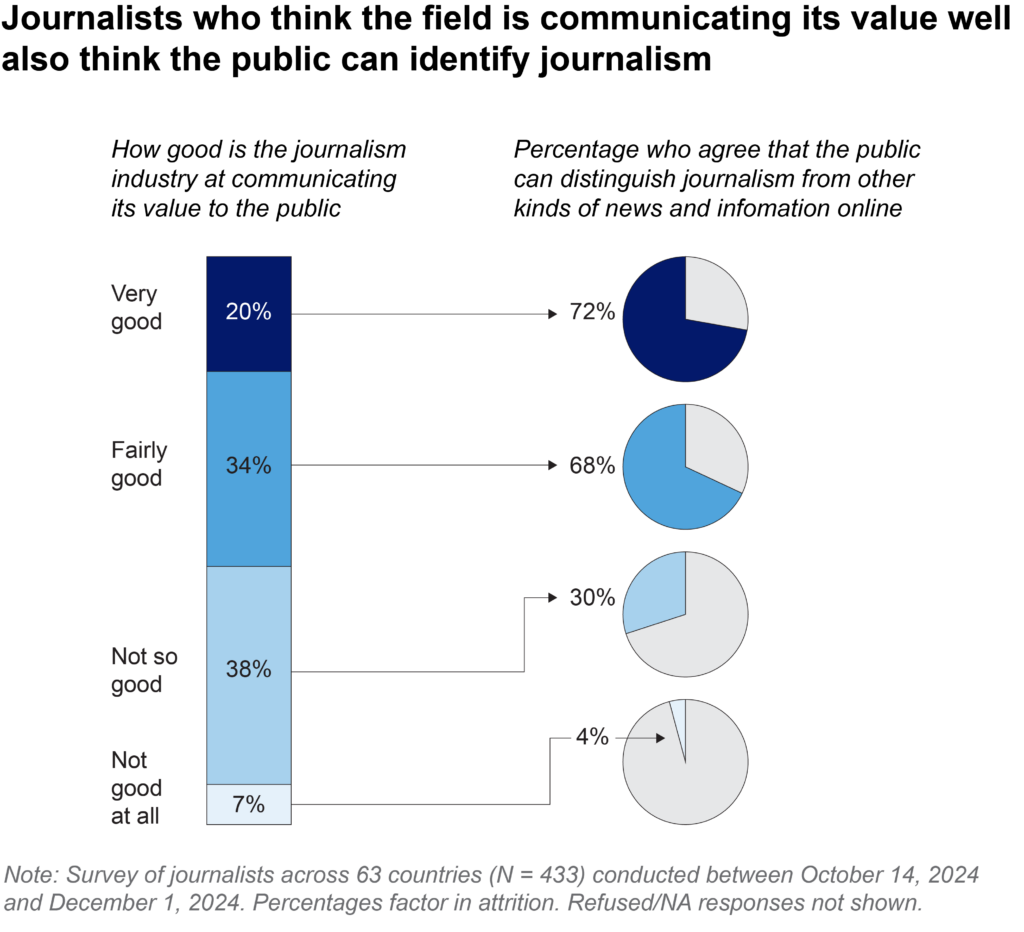

In this lens on how journalists themselves feel about their role in society, respondents mainly focus on the civic function of journalism — its power to support informed participation in public life — and the importance of broad circulation and distribution. But, nearly half of them (45%) think the field is not communicating that value well to the public, and a similar number (51%) think the public cannot identify what journalism is and what it is not. The traits journalists associate with their job — ethical standards, approaching things analytically, and working hard — clearly support the civic function of news. There are some differences by region. While those in the Global North are more likely to say non-journalists can produce journalism, most of the respondents find the public an important source for their work.

Why we did this study

This project continues CNTI’s Defining News Initiative seeking to understand how journalism is defined today. Access to information is not just important for its own sake; it makes democracy possible. In 2024, the United Nations outlined Global Principles for Information Integrity in response to growing challenges around misinformation, disinformation and hate speech.

This survey explores (1) how current journalists view their industry, (2) their (and their organizations’) uses and perceptions of technology, (3) their perspectives on government action and cyber security and (4) their experiences with online harassment and abuse. Importantly, respondents to CNTI’s study come from a global mix of journalists that provide an international perspective on how journalists are navigating and understanding their rapidly changing industry.

For more details, see “About this study.”

How we did this

CNTI partnered with journalism organizations in several continents to share the survey with their memberships. Surveys are a snapshot of what people think at a particular moment in time. These data were collected between October 14, 2024 and December 1, 2024, which means they highlight the perspective of journalists around the world during that time frame.

These data reflect the responses collected from 433 journalists across 63 countries. Because no global census of journalists exists, no survey can be “fully representative” of all journalists. Moreover, 256 of our respondents (59%) came from three countries: Mexico, Nigeria, and the U.S.; when one of these three countries is statistically different from others in its group, we acknowledge that difference in the text.

For this section, we grouped countries into Global North and Global South, which share many demographic, economic and political similarities. A little more than a third (38%) of our respondents live in the Global North, and the rest live in the Global South (62%).

Journalists see a lot of value in their field

We asked journalists to define journalism in just a few words. Of the 323 codeable answers in English, Spanish, French, Ukrainian, German, and Arabic,1 223 (69%) focus on the professional practice of journalism and 181 (56%) focus on the social function of journalism. These numbers add up to more than 100% because 88 responses (27%) address both. An additional nine responses mention other traits, including six that emphasize downsides of practicing journalism, like poor pay or high levels of risk.

Overall, journalists are most concerned with the civic function of journalism, under the theme of social function (i.e., its power to support informed participation in public life) and the importance of broad circulation and distribution, under the theme of professional practice. More than 75% of responses include at least one of these two concepts. Journalists also emphasize the importance of reliable facts (28%) and the process of newsgathering (25%) as defining professional norms.

Journalists define journalism in terms of both professional practices and social functions

| Theme: Professional practice | 69% |

| Distribution | 44% |

| Factual | 28% |

| Newsgathering | 25% |

| Verification | 15% |

| Objective | 8% |

| Theme: Social function | 56% |

| Civic | 48% |

| Watchdog | 12% |

| Interventionist | 5% |

| Service | 2% |

| Infotainment | 0 |

| Loyal facilitator | 0 |

| Other | 3% |

| Downsides of journalism | 2% |

Note: We coded a total of 323 responses, and answers were not mutually exclusive, so percentages add up to more than 100%.

Professional practice

The 223 responses about the professional practice of journalism are varied. At least 142 responses address distribution. A typical answer in this category “Journalism is the practice of disseminating timely and accurate information to the public,” highlights journalism as a process and profession dedicated to communicating, disseminating and reporting.

Professional practice theme

The Professional practice theme, which was synthesized from the responses, has five subcategories. The first three categories focus on processes that journalists follow, while the latter two emphasize professional norms.

- Journalism requires newsgathering. One core journalistic process is conducting research and investigation to learn about things that are happening.

- Journalism requires verification. A second core journalistic process is verifying and assessing the truth of that information before sharing it.

- Journalism requires distribution. A third core journalistic process is distributing or disseminating those stories. These responses typically focused on large-scale broadcast communication, which was almost always unidirectional.

- Journalism is factual. A core norm is that journalism is based on facts that are reliable and truthful.

- Journalism is objective. A core norm is that journalism is objective, fair, and independent of political or economic influence.

The next most common response is that journalism is factual (at least 91 responses), followed closely by newsgathering (81).

Newsgathering and distribution often co-occur in responses. One person writes, for example, “Journalism is a profession of gathering, processing and disseminating information through various mediums.”

At least 50 answers refer to verification, such as “The art of providing verified information to the citizens so they can be well-informed — and make well-informed decisions.” This concept frequently co-occurs with the norm that journalism must be factual. A typical response that includes both: “Collecting information, verifying it and bringing it to the attention of the public” (recueillir l’information, la vérifier et la porter à la connaissance du public).

Objectivity is a feature of at least 25 answers. As one person writes, journalism means “to make information of interest available to the public in a truthful and objective manner” (dar a conocer al público información de interés de manera veraz y objetiva).

Social function

The majority of responses about the social function of journalism focus on two of the six major roles of journalism outlined by the Journalistic Role Performance project: the civic and watchdog roles. At least 156 responses include the civic role. Many of these comments use language like “informing the public.” Meanwhile, at least 39 responses include the watchdog role. These two roles are highly compatible with one another, and many responses combine elements of both, such as the person who writes, “In pursuit of what benefits and serves the public interest of citizens, condemns violations, and strives to achieve justice.”

Social function theme

The Social function theme draws from the Journalistic Role Performance project. It focuses on roles of journalism as seen in published news reports, but their categories are also useful to understand how journalists describe their role. We analyzed the 181 responses that address the social function of journalism using these categories.

- Civic journalism empowers people to get involved in public debate and participate in public life, often by highlighting local impact and contexts.

- Watchdog journalism focuses on holding powerful people and institutions accountable by uncovering hidden truths and secrets.

- Interventionist journalism includes the journalist’s voice and includes forms of journalism that advocate for particular people or groups.

- Service journalism focuses on “news you can use” for individuals.

- Loyal facilitator journalism promotes and defends government actions and policies and encourages patriotism.

- Infotainment journalism is frequently lurid or morbid and serves to shock and entertain.

Only a small number of responses point to the other roles. At least 15 include the interventionist role. Many of these responses focus on journalism’s ability to support development or offer solutions to social problems. The five we categorized under service point explicitly to journalism’s role in supporting decision-making beyond politics and government. All of these also refer to the civic function of journalism, such as the person who writes, “Giving people the information they need to make good decisions about their lives, their governments and their financial interests.”

Both the infotainment and loyal facilitator roles are roles that journalism sometimes plays in the world, but they are not necessarily compatible with the ideals of journalism. It is no surprise, then, that we do not see any responses that spoke to either. However, three responses that focus on the civic function of journalism also nod to “entertainment” as one of several functions that journalism could provide, like the person who writes that journalism is “Collecting, choosing, writing/speaking news for the audience, enable them to form an opinion or get entertained.”

Other considerations

At least six journalists who do not provide clear definitions focus instead on downsides of practicing journalism, including risk to practitioners and poor pay. As one person writes, “A nice exercise because it addresses the needs of the population, but one that is very risky at present.” (Un ejercicio bondadoso porque se suma a las causas de las necesidades de la población, pero de mucho riesgo en la actualidad.)

Nearly half of journalists think the industry is failing to communicate its value — which leads to public confusion

As the definitions above make clear, journalists see a lot of value in their field. But there is less consensus over how well they think the journalism industry is communicating that value. Only two-in-ten say the industry is doing a “very good” job communicating its value to the public while about three-in-ten say it’s doing a “fairly good” job and a similar number say “not so good.” Journalists in the Global North are much more negative than journalists in the Global South: just 2% of journalists in the Global North say the industry is doing a very good job, compared with 30% in the Global South. It is also important to note some stark national differences: journalists in Nigeria are much more positive than journalists elsewhere in the Global South. More than half of them say the industry is doing a “very good” job.

Just about half of journalists think the public cannot differentiate journalism from other kinds of news and information

Respondents are just about evenly split on whether they think the public can tell the difference between journalism and other kinds of news and information online: 49% say "yes" and 51% say "no."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the journalists who think the industry is communicating its value well are also much more positive about the public's ability to distinguish journalism from other news and information. A strong majority (68-72%) of those who say the industry is doing a fairly good or very good job of communicating its value say that the public can distinguish these categories of information. Just 4% of those who say the industry is not doing a good job at all agree.

51%

of journalists think the public cannot tell the difference between journalism and other kinds of news and information online.

Journalists in the Global South are more likely to say the public can tell the difference between journalism and other forms of news: 55% of them agreed, compared with 40% in the Global North. And, looking at specific countries, journalists from the United States stand out as the most pessimistic. About one-in-four U.S. journalists surveyed thinks the public can distinguish journalism from other kinds of news and information. Meanwhile, half of Mexican and 70% of Nigerian journalists surveyed think the public can.2

Journalists in the Global South are also much more positive about social media overall (see Technology & AI section). One potential reason for these views could be the vast development of alternative news sources in the digital space, alongside the rise of disinformation that intentionally mimics news media in form.

CNTI's related report on the public's views of journalism offers some interesting areas of contrast. In that work, we find that publics in the Global South are less likely to draw a distinction between news and journalism. But here we see clearly that journalists in the Global South are more likely to say they do.

Professional training and institutions matter to journalists' self-conception

Despite the growing presence of and reliance on news influencers — most of whom are unaffiliated with news organizations — most journalists who took our survey think that being a journalist requires having a specific type of formal education, working for a news outlet, or both. More than eight-in-ten say that "formal education and training" is somewhat important or very important, and three out of four say the same about "working for a news organization." Indeed, over eight-in-ten journalists surveyed here work for news organizations.

Journalists in the Global South feel more strongly about both education and working for a news outlet

Journalists in the Global South feel more strongly than those in the Global North that formal education and training are very important (75% versus 32%), with much of the difference driven by specific countries within each region. Journalists in Nigeria feel particularly strongly about formal education: 91% say it is "very important."

Similarly, 22% of journalists in the Global North say that working for a news organization is very important, and 51% of their Global South colleagues say the same. Journalists in Nigeria (67%) are more likely to say that it is very important, compared with journalists elsewhere in the Global South.

A slim majority of journalists say that people who are not journalists can produce journalism; overwhelming majorities see information from the public as important to their work

While most journalists surveyed say that journalists have to work for news organizations, a majority of respondents (58%) also say that people who are not journalists can produce journalism. In the Global North a strong majority (66%) feel this way, compared with half (53%) in the Global South. Countries within each region are consistent with one another.

The public seems to agree: CNTI’s survey of publics in four countries found that nearly three-quarters in the Global North (specifically, the U.S. or Australia) think that people who are not journalists can produce journalism. Meanwhile, about half of Brazilians and South Africans say the same.

Journalists say news and posts from the public are important to their work — especially in the Global South

All the same, information coming from the public is important to journalists' work – 88% say it is at least somewhat important, and 47% say it is very important. In the Global South, where more people say that journalists can produce journalism, information from the public is even more important. Journalists in Mexico say this is even more important than others in the Global South.

Overall, journalists in the Global South are stricter about qualifications than those in the Global North but they place more importance on news and information posted by members of the public. These findings at first seem contradictory, but they speak to an understanding of journalists as gatekeepers who verify, curate and disseminate information with help from the public, when appropriate.

Journalists use similar terms to describe traits of journalists as they do to define the job

In addition to asking for definitions of the field, we asked about the people who do this work. We asked the journalists who took our survey to list the top three traits or characteristics they most associate with the job of a journalist. We received answers from 351 different people in six languages, of which 325 sets of responses could be analyzed.3

The traits respondents identify largely comport with the definitions of the field. The traits identified in this survey also align closely with the themes identified in our earlier focus groups.

The majority of answers fall into eight somewhat fuzzy categories. A full list of words associated with each category is included in “About this study.”

Journalists rely on verifiable facts and have clear ethical standards

| Category | % |

|---|---|

| Rely on verifiable facts | 49% |

| Clear ethical standards | 41% |

| Objectivity | 26% |

| Analytical | 28% |

| Grit and hard work | 24% |

| Mental acumen | 24% |

| Communicate complicated topics clearly | 22% |

| Timely and proximate | 20% |

Note: Survey of journalists across 63 countries (N = 433) conducted between October 14, 2024 and December 1, 2024. Percentages add up to more than 100 because each individual could provide up to three responses and because some lengthy responses were coded as containing multiple concepts.

- Journalists rely on verifiable facts. Journalists tell stories that are truthful and that rely on details that can be confirmed. Journalists and the stories they tell are credible, accurate and reliable. Some other words and phrases associated with this trait include "fact(ual)," "truth(ful)" and "trust(worthy)." At least 159 individuals (49%) mention this trait.

- Journalists have clear ethical standards. They approach their work following a set of professional standards. They are independent from governmental and other kinds of interference, even incorruptible. Moreover, they are transparent and honest in their dealings, and focus on what is in the public interest. Other words and phrases that speak to this concept include "accountability," "sincerity" and "watchdog." At least 134 respondents (41%) included this trait.

- One particular facet of journalistic ethics stood out in our data: objectivity. Journalists are neutral, impartial and fair. Their work attempts to present all sides of an issue or incident, including multiple points of view. Other cues to this concept include "balance" and "unbiased." At least 86 journalists (26%) include this trait.

- Journalists are analytical. They engage in processes of research, investigation and analysis. They are skeptical of what they are told and approach information with critical thinking. Additional cues to this concept include "gather" and "context." At least 90 journalists (28%) include this trait.

- Journalists have "grit" and work hard. They approach things multiple times through different channels, rather than stopping when the work gets difficult. They are persistent and "tenacious, and face challenges with courage." Some additional words and phrases associated with this trait include "determination," "passion," "thorough," "commitment" and "responsibility." At least 78 respondents (24%) include this trait.

- Journalists have mental acumen. They are intelligent, knowledgeable, educated and curious about the world. At least 77 journalists (24%) include this trait.

- Journalists can communicate complicated topics clearly. They are excellent at writing and storytelling and take a creative approach. Other ways we saw this trait expressed were in terms of "clarity." At least 72 people (22%) mention this trait.

- Journalists provide work that is timely and proximate to happenings on the ground. Journalists work quickly and are able to pivot. They are physically present at the scene whenever possible, and have access to sources and connections who witnessed specific events or have access to insider information. Some of the words and phrases associated with this trait include "immediacy," "deadlines," "be at the scene of the incident," "sources" and "adaptability." At least 66 individuals (20%) mention this trait.

These traits of journalists overlap considerably with respondents’ definitions of journalism. In particular, the emphasis on verifiable facts and objectivity across both questions underscore that these are core to journalists' perceptions of their own field. Moreover, there is a clear throughline between these traits and journalists' emphasis on the civic function of journalism, which about half (48%) reference in their definitions.

Continue reading:

- Overview

- Government: Journalists are not comfortable with government involvement

- Technology: Journalists believe technology is improving their work, but they are less sure about AI

- Security: One in three journalists regularly face serious risks, but their level of preparedness varies; most want to talk about it

- About this study

Read CNTI’s companion report based on surveys with representative publics in four countries.

- Thirty responses were too brief or ambiguous to code. ↩︎

- These are the three countries from which we received sufficient responses to look at them individually. We call them out only in cases like this one, where we see meaningful differences from the larger region. See “About this study” for further details. ↩︎

- The other answers were unclear, or did not seem to respond to the question that was asked. ↩︎

What It Means to Do Journalism in the Age of AI

Share

Additional Work

-

AI Transcription and Translation in Journalism

Working Group Briefing #2: November 2025

-

CNTI Newsgeist 2025: Trust, Truth and Innovation in a Shifting Industry

From October 10 to 12, 180 participants gathered in Phoenix, Arizona, for the first CNTI-led Newsgeist.

-

Most people in four countries describe journalists positively

Strong majorities in Australia, Brazil, South Africa and the US use only favorable terms to describe journalists' traits